TL;DR

- After emerging at the start of the pandemic, Chinese-language money laundering networks (CMLNs) now dominate known crypto money laundering activity, processing an estimated 20% of illicit crypto funds over the past five years. This growth is 7,325 times faster than growth of illicit inflows to centralized exchanges since 2020.

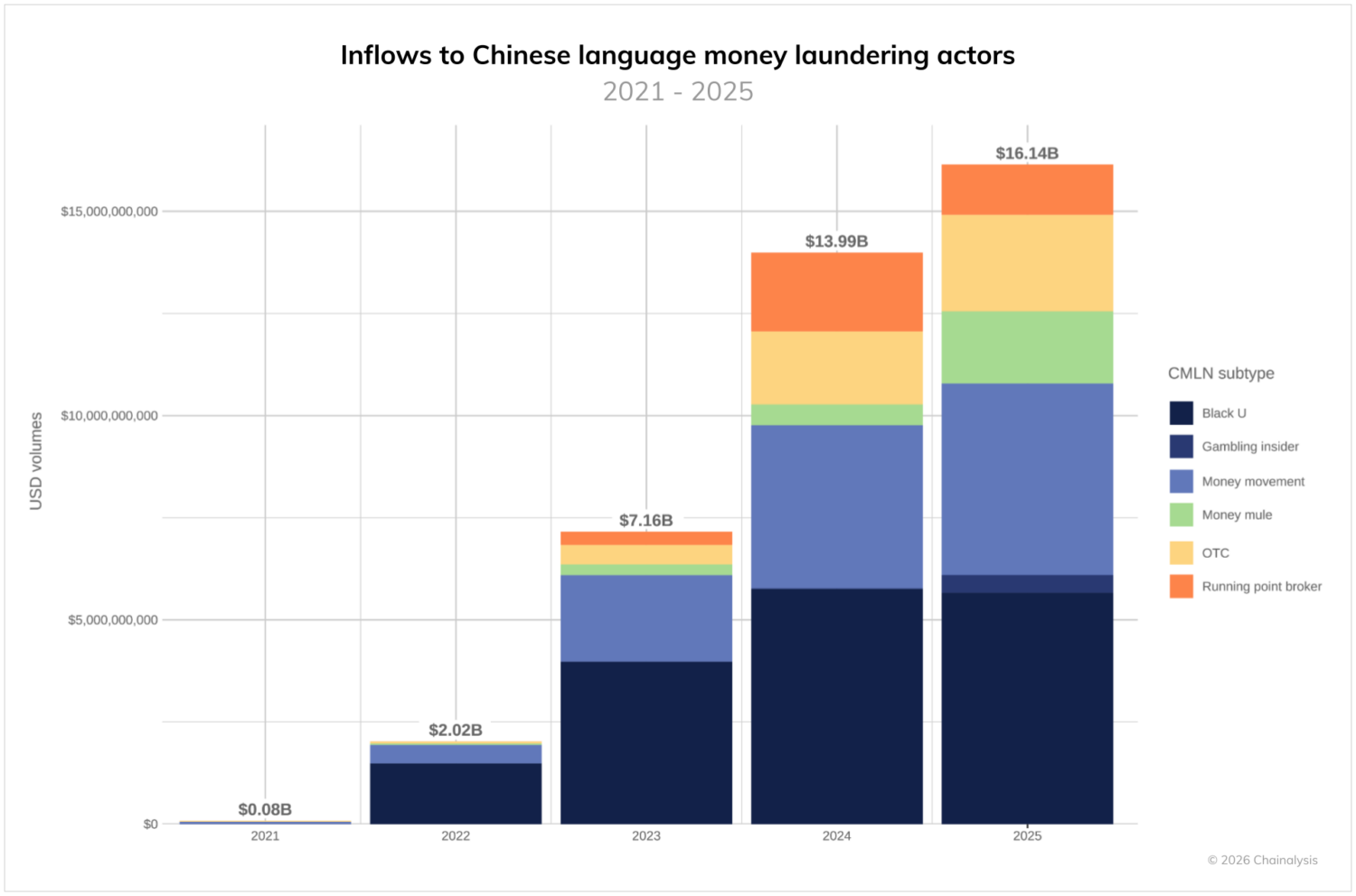

- CMLNs processed $16.1 billion in 2025 — approximately $44 million per day across 1,799+ active wallets.

- Chainalysis has identified on-chain behavioral fingerprints of six distinct service types within the CMLN ecosystem. Black U and gambling services fragment large transactions into small amounts to evade detection, while over-the-counter (OTC) services consolidate small transactions into large amounts for integration.

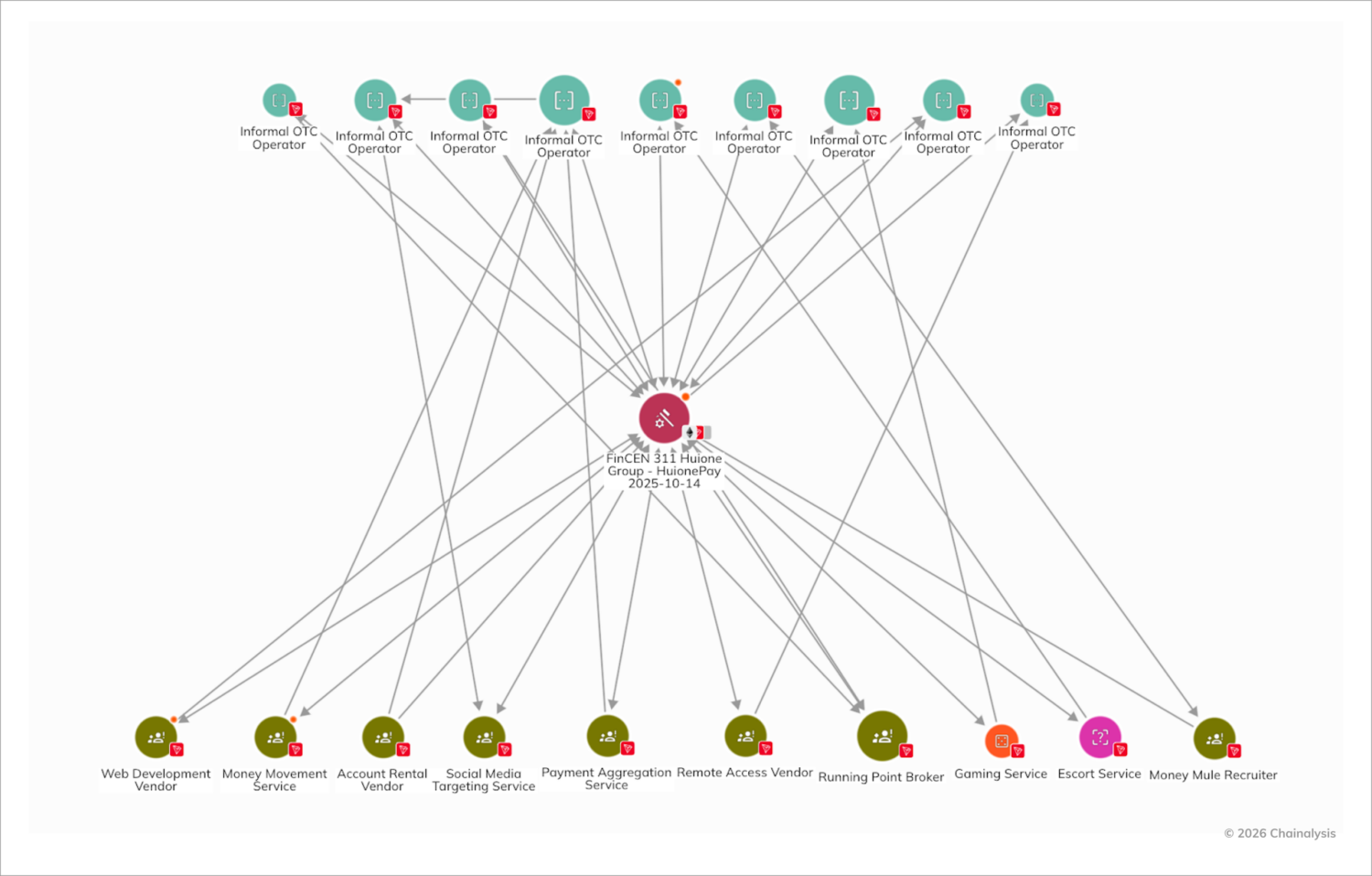

- Guarantee platforms like Huione and Xinbi serve as aggregation points for money laundering vendors, but don’t control underlying activity, and therefore are not included in our total metric. Enforcement actions have proven disruptive, but vendors simply migrate to alternative channels, highlighting the need to target laundering operators themselves.

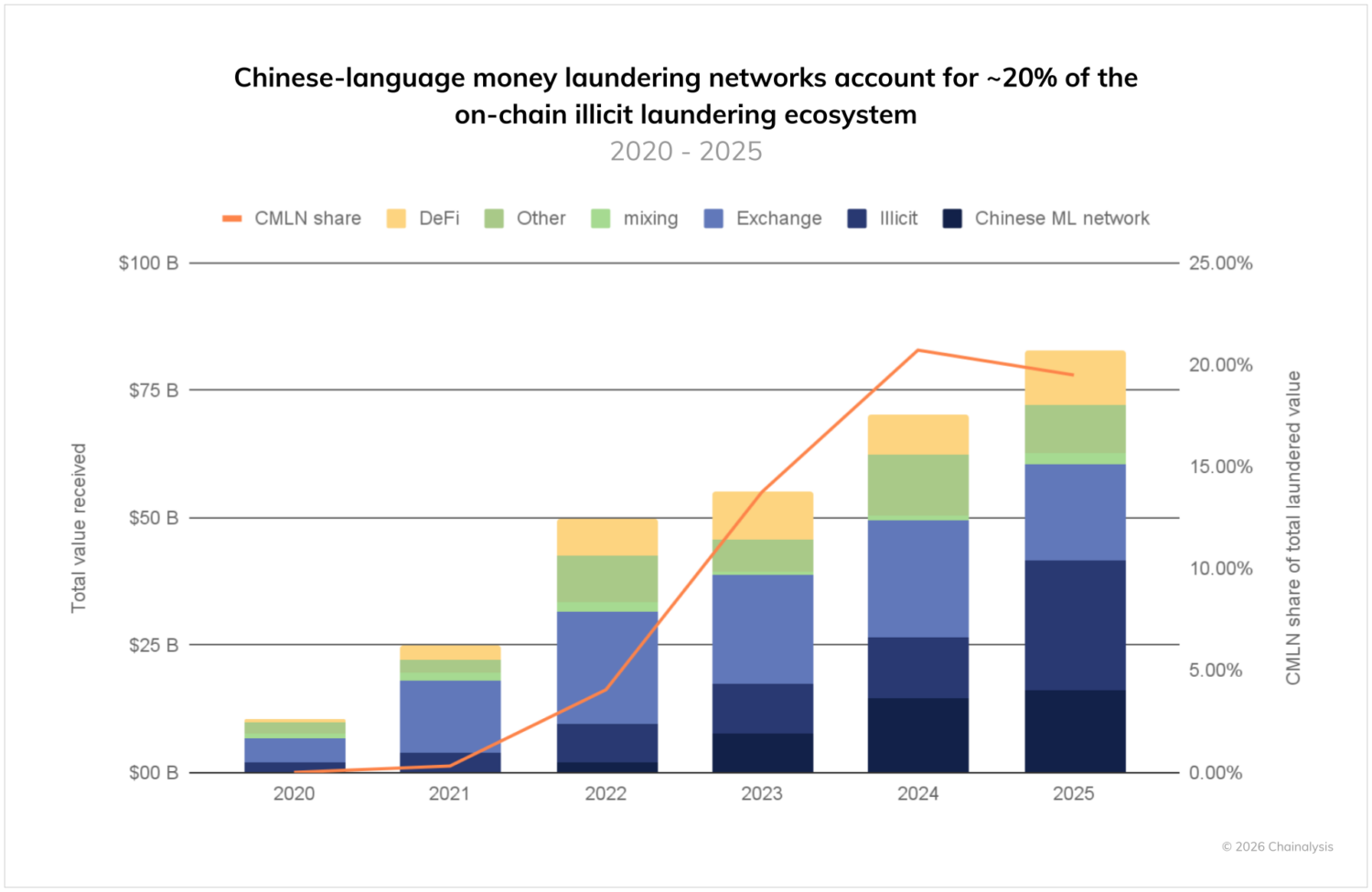

The illicit on-chain money laundering ecosystem has grown dramatically in recent years, increasing from $10 billion in 2020 to over $82 billion in 2025. [1] This substantial topline growth reflects the growing accessibility and liquidity of cryptocurrencies, as well as a fundamental shift in how this laundering activity occurs and by whom.

As shown in the chart below, Chinese-language money laundering networks (CMLNs) have increased their share of known illicit laundering activity to approximately 20% in 2025. This regional connection is further evidenced by the off-ramping patterns we observe. To take one example, as we highlighted in the scams chapter of this report, CLMNs have grown to now consistently launder over 10% of funds stolen in pig butchering scams, coinciding with a steady decline in the use of centralized exchanges, potentially because exchanges can freeze funds.

Compared to other laundering endpoints, since 2020, inflows to identified CMLNs grew 7,325 times faster than those to centralized exchanges, 1,810 times faster than those to decentralized finance (DeFi), and 2,190 times faster than intra-illicit on-chain flows. While CMLNs are by no means the only facilitator of on-chain laundering, Chinese-language Telegram-based services now account for a disproportionate share of the attributed global on-chain money laundering landscape. In doing so, they process funds from a wide range of on- and off-chain criminal activity.

Recent enforcement actions against money laundering facilitation networks, including sanctions designations and advisories, have shined a light on the national security threat impacting victims worldwide. These actions include the designation of the Prince Group by the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) by HM Treasury in the UK, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)’s Final Rule designating Huione Group as a primary money laundering concern, and FinCEN’s advisory on Chinese money laundering networks.

While these major facilitators have rightfully been attracting more attention in recent months, this chapter for the first time takes a deeper look at how these extensive underground laundering networks use cryptocurrency and analyzes the scale of these ecosystems. These money laundering networks operate openly across various platforms and demonstrate complex, multi-layered operations characterized by industrial-scale processing capacity, operational resilience, and technical sophistication.

The $16.1 billion scope and scale of CMLNs

We have identified six discrete service types that make up the CMLN ecosystem, which we will examine in the sections ahead. Together, these services processed $16.1 billion in inflows in 2025. The number of active entities that comprise these networks has risen from a small handful only a few years ago to over 1,799 active on-chain wallets in 2025.

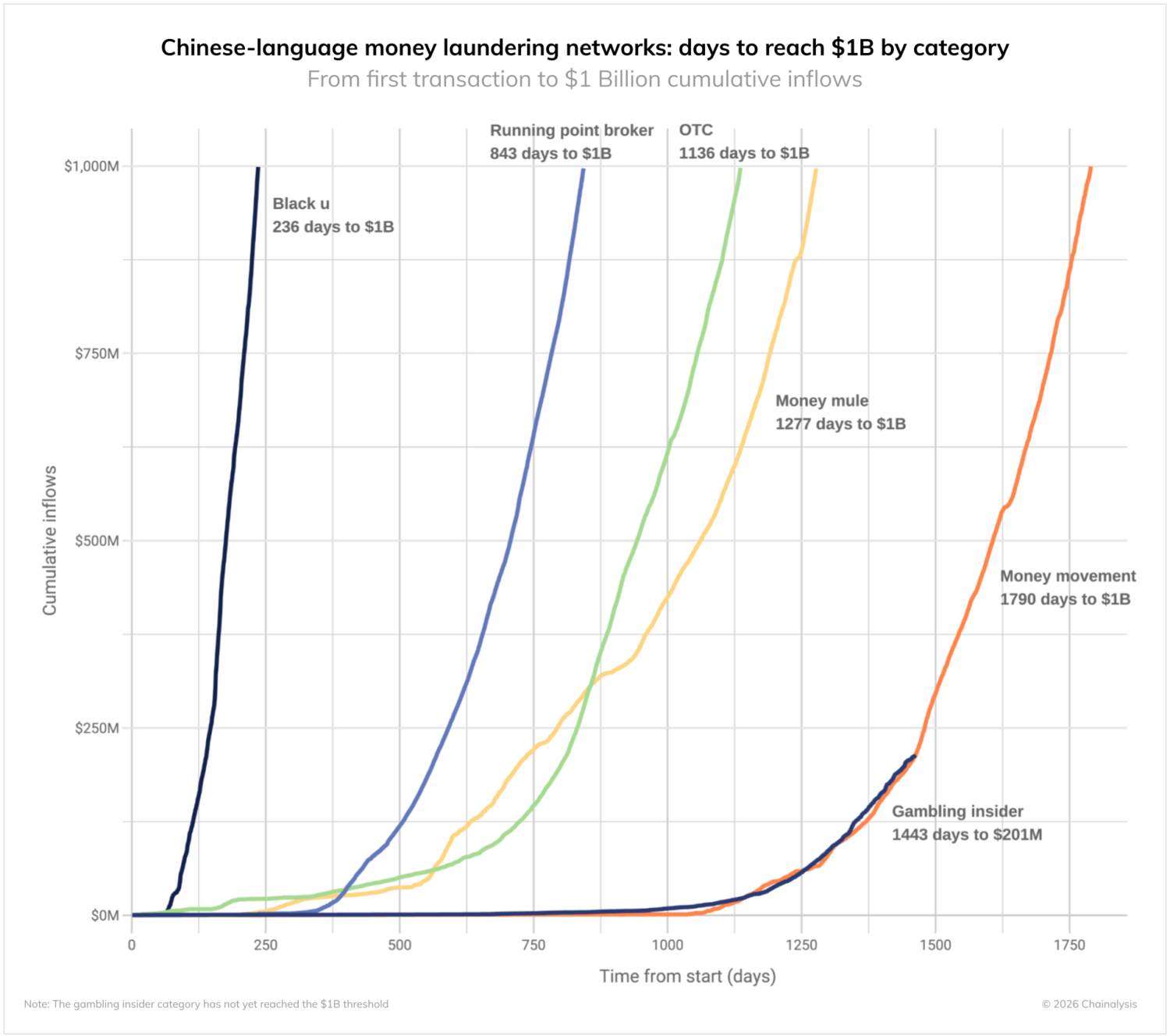

The speed to scale of these operations is equally concerning. The time it takes for each service type to process $1 billion since the first known address of its category receives funds reveals both a remarkably rapid time-to-scale and striking differences between service types. Black U services reached this milestone in just 236 days, while running point brokers required 843 days and OTC services 1,136 days. Money mules (1,277 days) and money movement services (1,790 days) operate more slowly, while gambling insider services have yet to reach the billion-dollar threshold. Overall, the CMLN ecosystem in 2025 is processing almost $44 million per day.

These networks’ rapid time-to-scale suggests they are tightly interwoven with off-chain criminal networks, as growth of this magnitude would be hard to achieve without significant capital pools put into play. It also reveals a sophisticated on-chain and off-chain operational infrastructure. At the center of this ecosystem sit guarantee platforms — centralized marketplaces that have become the anchor for CMLN operations.

As Tom Keatinge, Director at the Centre for Finance & Security (CFS) at RUSI, told us, “Very rapidly, these networks have developed into multi-billion dollar cross-border operations offering efficient, value-for-money laundering services that suit the needs of transnational organized crime groups across Europe and North America. As to why these networks have developed so fast, the short answer is that they are an unforeseen consequence of the imposition of capital controls in China. Wealthy individuals seeking to move money out of China and evade these controls provide the impetus and liquidity pool needed to service organized crime groups based in the West. The professional enablers of this capital flight provide the services necessary to match these two independent yet mutually beneficial needs.”

Similarly, Chris Urben, Managing Director at Nardello & Co explained to us that “the biggest change in Chinese money laundering networks in recent years is a rapid transition to crypto from reliance on informal value transfer systems like the traditional Black Market Peso or Fei Qian approaches to underground banking. Crypto offers an efficient way to discreetly move funds across borders without having to rely on the complex manual network of informal ledgers in various countries that used to be the norm.”

Guarantee platforms: the anchor of the CMLN ecosystem

Guarantee services function primarily as marketing venues and escrow infrastructure for CMLNs. While they provide trust mechanisms for vendors, they don’t control the underlying laundering activity and aren’t included in our total metric. Huione and Xinbi have dominated the market for the past few years, and many other guarantee services continue to operate freely.

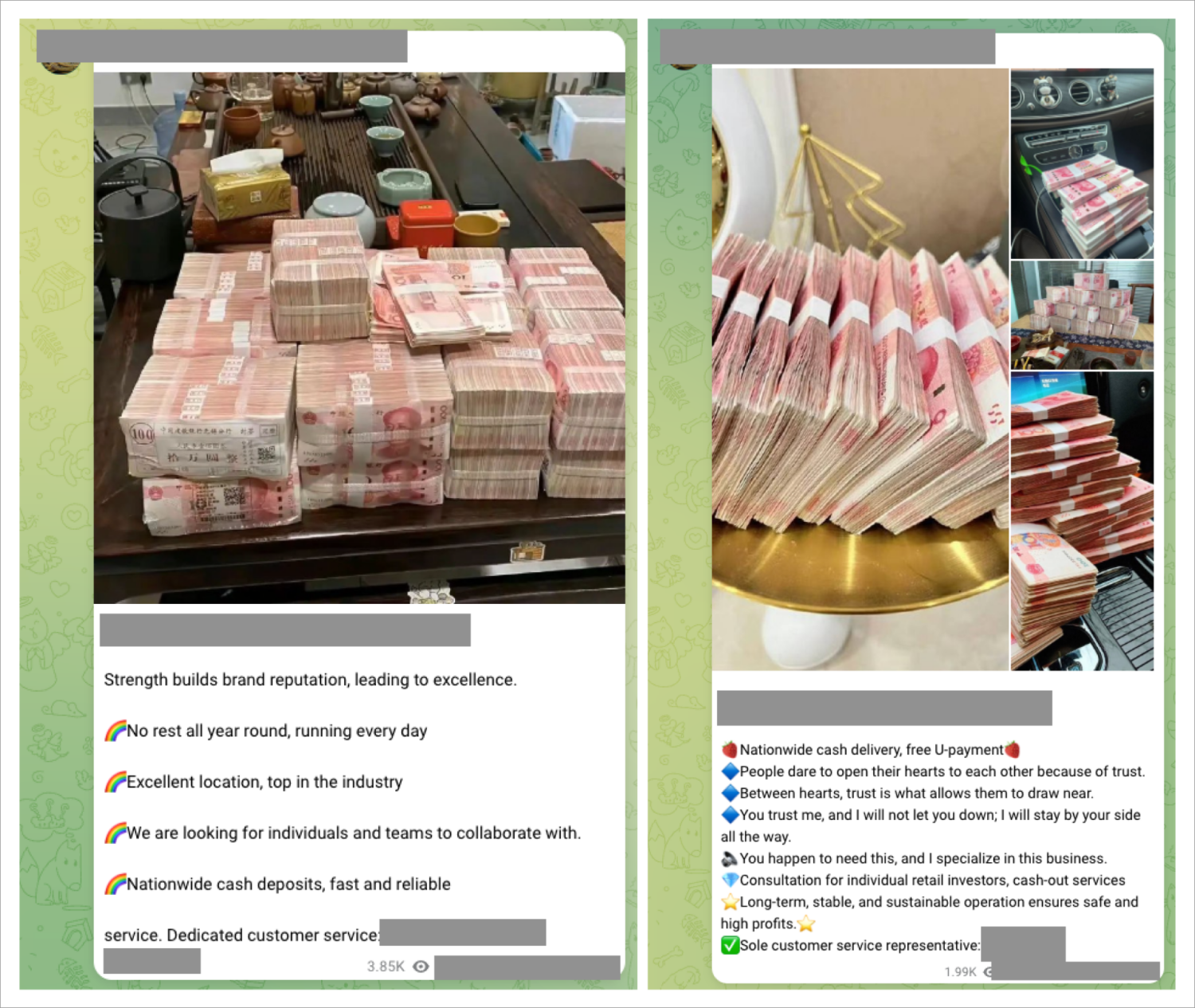

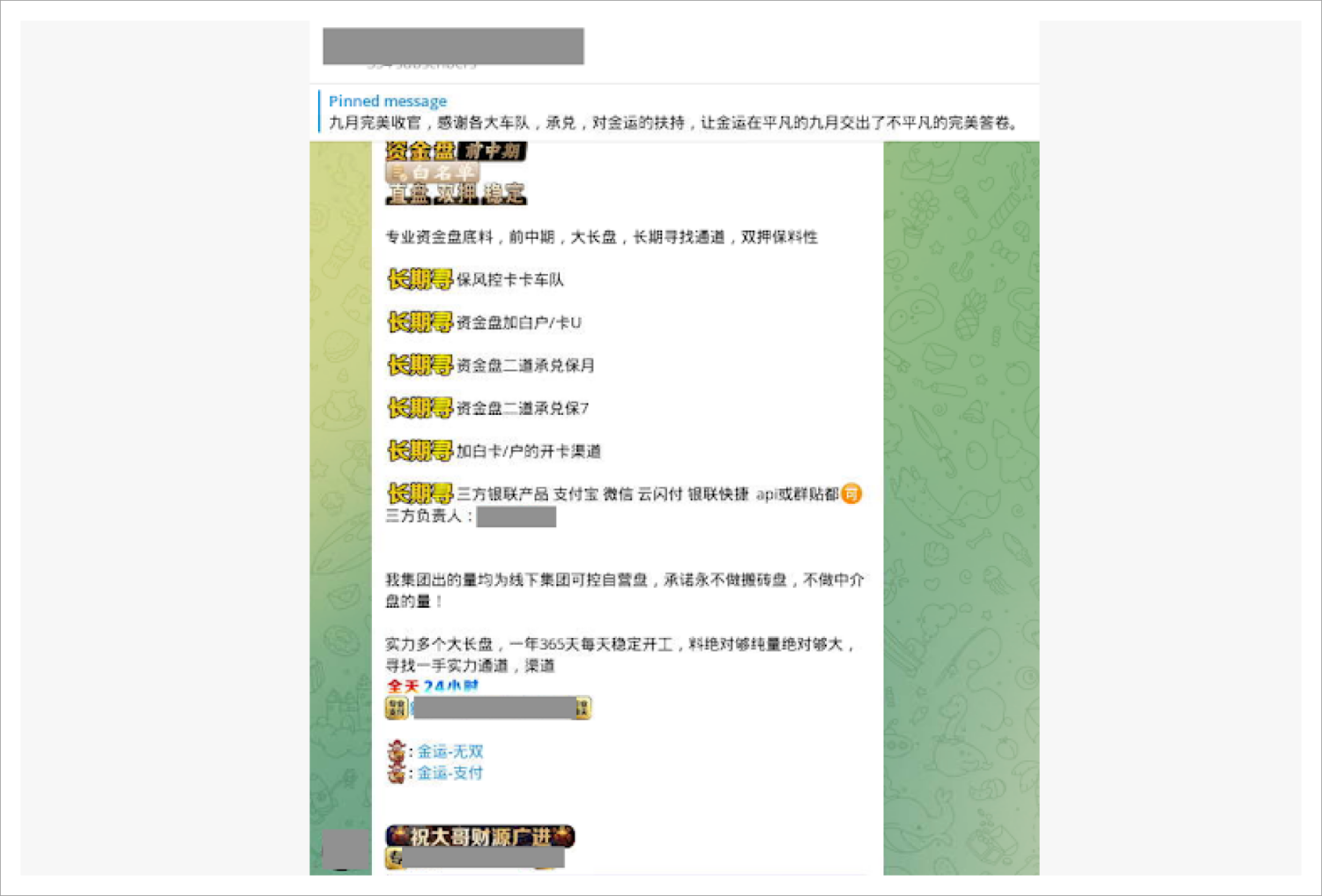

While Huione’s guarantee operations were disrupted after Telegram removed some of their accounts, vendors using Huione have continued to use or advertise on alternative platforms, their operations uninterrupted. While these hubs continue to connect vendors and buyers, most vendors promote advertisements across platforms and are not reliant on any specific service. As with legitimate e-commerce platforms, service ratings and reviews create accountability within the illicit ecosystem, and vendors often cultivate their market reputation through public attestations of their reliability and service quality, as shown in the screenshot below.

CMLNs advertising on these guarantee services offer a range of money laundering techniques with the primary goal of integrating illicit funds into the legitimate financial system. Some leverage vast networks of money mules for access to mainstream crypto exchange laundering, while others operate their own on-chain laundering infrastructure. These laundering methodologies represent distinct approaches to achieving the same goal: cleaning dirty money.

The six CMLN typologies

CMLNs offer a wide variety of laundering-as-a-service businesses. Our analysis of Chinese-language vendor posts reveals that these services deploy six primary money movement techniques: running point brokers, money mules, OTCs, Black U services, gambling platforms, and money movement services that offer mixing and swapping of crypto assets. These operations involve thousands of vendors processing tens of billions of dollars. Understanding how these entities operate and form a comprehensive laundering network provides crucial insights into potential disruption opportunities. Below, we examine these service categories in detail.

1. Running point brokers: the initial entry channel

In the money laundering process, “running points” (跑分) serve as the critical entry channel for illicit fund transfers. Individuals are recruited, typically through vendor advertisements, to rent out their financial identities, providing bank accounts, digital wallets, or deposit addresses at mainstream exchanges to receive and forward fraudulent proceeds.

Advertisements explicitly warn participants that they bear all legal consequences and economic losses when authorities intervene, leaving no doubt that the activity is illicit.

Originally concentrated in online gambling operations, running points’ services have expanded to facilitate the full spectrum of illicit activities that leverage crypto for laundering, including romance scams, exchange heists, and Telegram-based human trafficking operations. This broad adoption reflects their fundamental utility: they provide the crucial bridge between legitimate financial systems and the criminal underground.

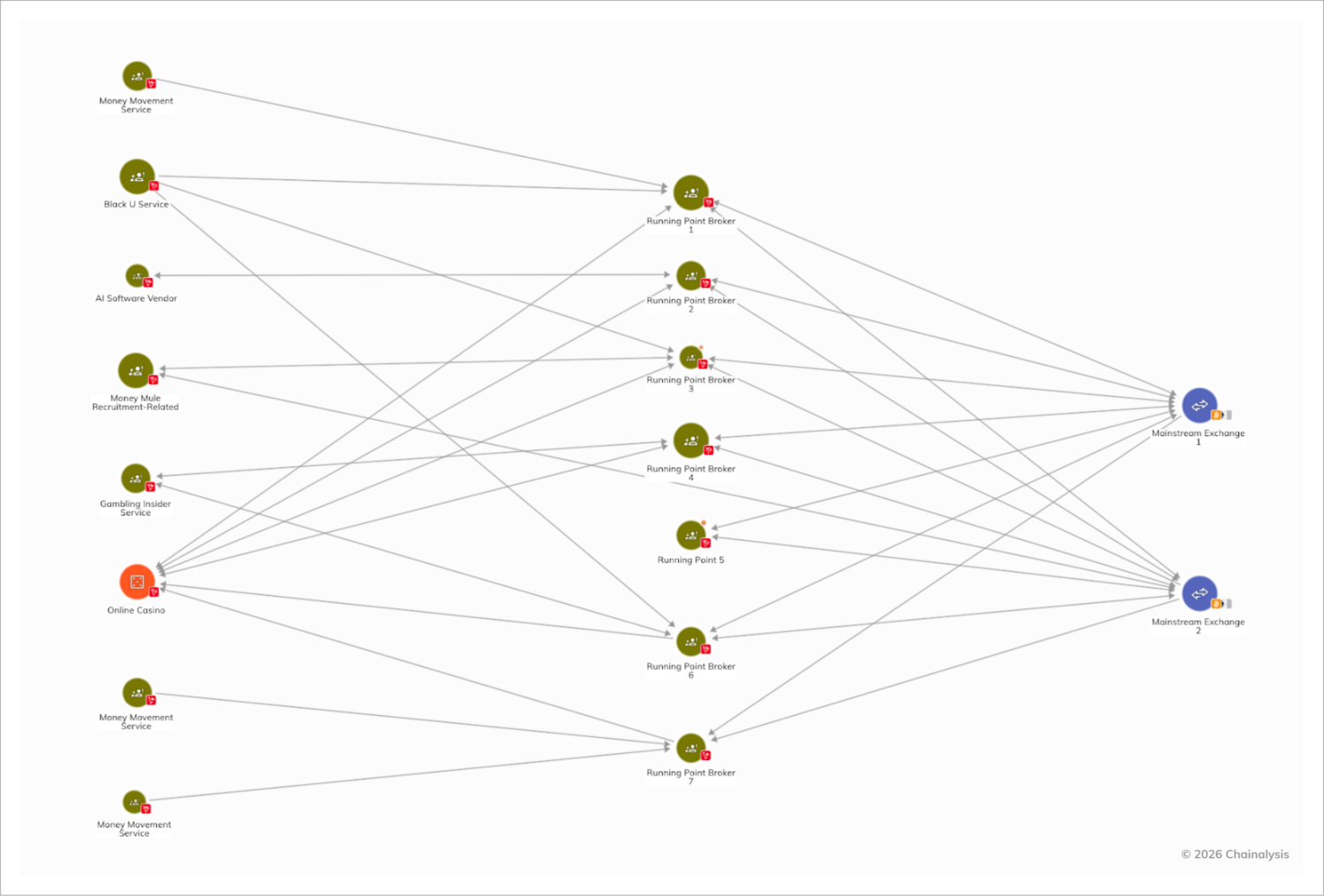

As illustrated in the Chainalysis Reactor graph below, running point brokers function as routing mechanisms for various illicit sources, ultimately sending funds to accounts — likely under a mule’s name — at mainstream exchanges. Notable destinations include other laundering services, mainstream exchanges to convert to fiat, and platforms associated with the Huione Group ecosystem.

2. Money mule motorcades: the laundering intermediaries

While “running points” serve as access points to exchanges, money mules, or “motorcades,” (车队) orchestrate the complex layering phase of money laundering. These specialized operators form networks of accounts and wallets to obscure fund origins through multiple transactions.

Money mule operations use a number of methods to convert between fiat and crypto, and vice-versa.This includes offline services where dealers meet customers in person; ATM cash withdrawals converted to crypto; digital wallet transfers through third-party payment platforms, and card-based schemes using credit cards and gift cards in exchange for crypto. Vendors openly advertise accepted financial institutions, crypto exchanges, and payment methods, although the actual arrangements with card merchants and intermediaries occur privately outside public Telegram channels.

Although we are unable to ascertain the nationality of the money mule motorcades based on Telegram posts alone, these posts are almost exclusively in Mandarin and often allude to bank accounts and locations in Mainland China, suggesting these money laundering vendors are likely primarily serving Chinese-speaking clientele. Recent research from the Royal United Service Institute (RUSI) has pointed to the growing involvement of Chinese organized crime. These networks, as well as legitimate crypto use, have continued to thrive in spite of China’s sweeping crypto ban. Chinese authorities have focused on selective crackdowns and AML enforcement – tacitly allowing or ignoring some forms of crypto activity while aggressively targeting anything that threatens the country’s capital controls or financial stability.

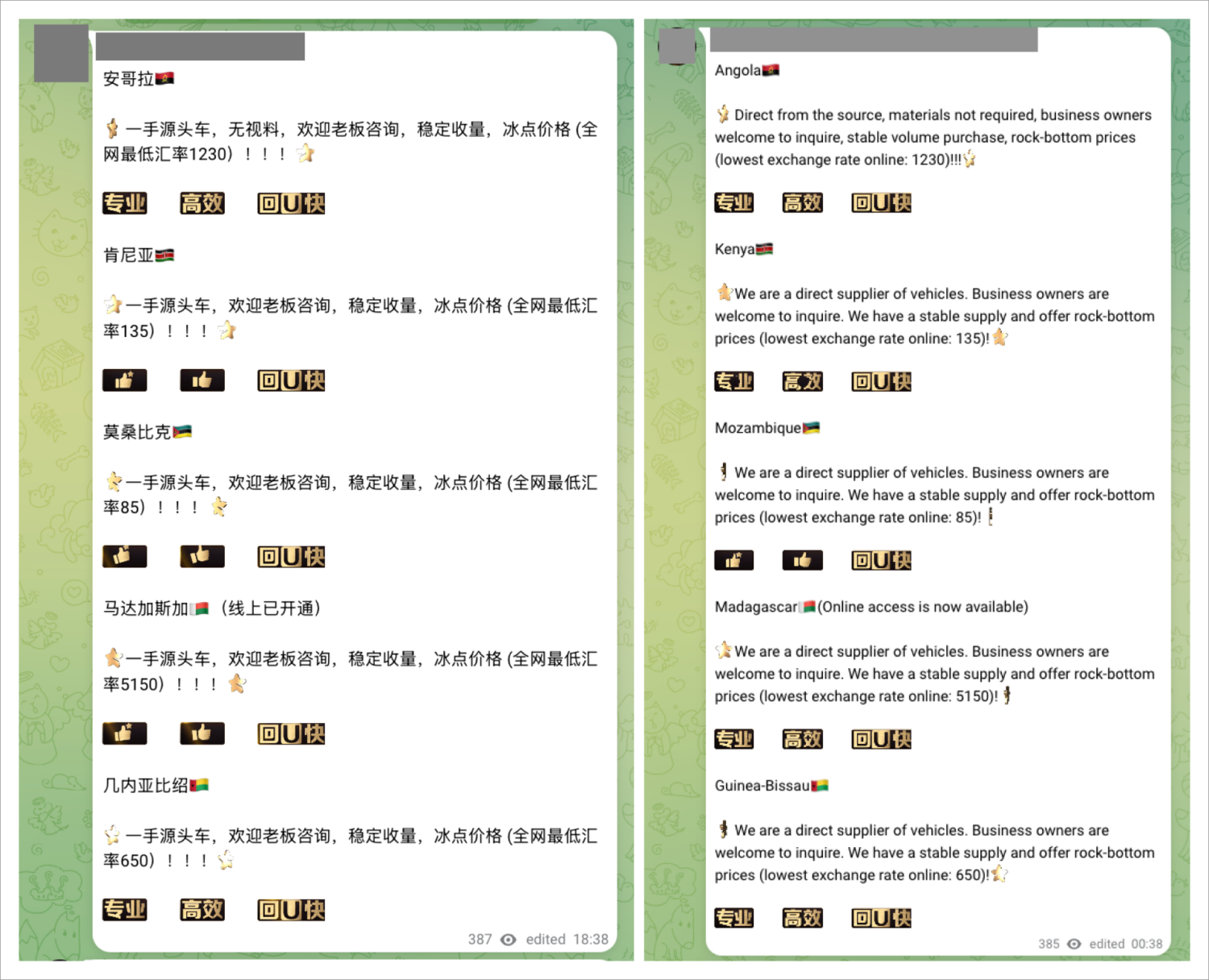

Beyond domestic operations, these networks readily offer specialized services for cross-border funds transfers through global payment methods and foreign currencies. Vendor operations boast their significant geographical reach. In Telegram posts, certain vendors claim to be able to coordinate “fleets” (likely referring to collections of motorcades and money mules) across Africa, suggesting the global reach of CMLN operations is growing well beyond China and East Asia. “CMLOs rightly view crypto as having less Know Your Customer compliance than traditional banks and crypto transactions, which decrease the risk and increase the speed of the laundering process,” notes Urben. “Finally, crypto makes it far easier to physically move large holdings across borders: you can carry billions of BTC in a cold wallet stored on a hard drive stuffed into your pocket.”

A recurring theme across advertisements offering money movement services is the pronounced emphasis on urgency, discretion, and speed. Vendors often stress the need to transfer funds rapidly to prevent fund freezes, while offering cursory guidance to their customers on navigating complications arising from funds and accounts that have already been restricted by financial institutions and crypto exchanges.

Within guarantee platforms, the movement of funds orchestrated by running point brokers and money mules constitute a large portion of the advertised offerings. The striking similarities in how advertisements are worded and structured suggest that these operators likely function either within larger umbrella organizations or maintain strategic collaborative relationships with one another. Collectively, these money movement services form the backbone of the money laundering infrastructure within the underground banking ecosystem.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) provides the most apt description of this relationship: motorcades function as extensions of running point syndicates, offering sophisticated layering schemes by routing illicit funds through multiple bank accounts in exchange for a cut of the total transferred funds. The UNODC’s 2024 report on casinos, money laundering, and transnational organized crime in East and Southeast Asia also highlights the use of third-party and fourth-party payment providers. These networks often indicate high levels of connectivity, suggesting layers of payment services may be operating as fronts by the same groups to facilitate laundering.

3. Informal over-the-counter (OTC) and peer-to-peer (P2P) services: Circumventing controls

Informal OTC trade desks offer another critical laundering pathway. Unlike their legitimate counterparts, these services operate without regulatory oversight or jurisdictional affiliation and deliberately circumvent capital controls required in highly controlled markets, such as China. By processing fund transfers without Know Your Customer (KYC) verification, they present an attractive option for users seeking to move assets, especially those of suspicious origins.

Many OTC vendors explicitly advertise “clean funds” or “White U.” Exchange rates displayed transparently in vendor posts often exceed market rates, reflecting the premium charged for regulatory evasion. These services process both domestic and cross-border transfers, expanding the geographic reach of illicit fund flows.

However, on-chain analysis contradicts “clean fund” claims. These supposedly legitimate OTC services maintain extensive connections with Huione and other guarantee platforms, revealing their deep integration within the broader CMLN ecosystem. The same vendors advertising “White U” regularly interact with confirmed money laundering services, demonstrating that informal OTC desks can function as critical bridges for illicit cryptocurrency.

4. Black U services: Discounted rates for tainted assets

Operating primarily outside guarantee platforms, “Black U” services occupy a unique niche in the CMLN ecosystem, and are the inverse of the informal “White U” OTCs. These vendors specialize in cryptocurrency derived from illicit sources, such as hacking campaigns, exploit attacks, scams, and wallet theft — and openly state this in their advertisements. Their business model involves selling illicit cryptocurrency at a discounted rate .

Buyers purchase illicitly sourced funds, sometimes 10-20% lower than standard rates in exchange for accepting assets with criminal provenance. This compensates buyers for assuming potential legal exposure and the risk of fund seizure.

The operational structure of Black U services reveals sophisticated coordination. Across different vendors, the front-end websites of Black U services often display nearly identical layouts with only superficial variations in domain names and branding. Telegram channels exhibit the same pattern. These infrastructural commonalities point to two possibilities: either these seemingly independent operations function as compartmentalized units within a single organization, or they represent a coordinated network maintaining operational consistency.

5. Gambling services: Traditional laundering goes digital

While not inherently illicit in many jurisdictions, gambling services have been used for both traditional and crypto-based laundering due to their high cash volumes, frequent transactions, and built-in mechanisms for converting funds. Both casinos and online betting platforms offer users an effective way to place, layer, and integrate proceeds into the legitimate financial system, especially because they provide plausible explanations for sudden wealth.

Many of these gambling services accept crypto and do not require KYC details. Third-party payment providers facilitate account top-ups using both fiat and crypto, with some processors handling recharges across multiple gambling sites, allowing for cross-platform fund movement. Additionally, some Telegram vendors offer insider tips suggesting predicted or rigged outcomes, with advertisements guaranteeing compensation if customers’ “winning numbers” are not selected. This further suggests that some gambling services are not just a conduit for laundering, but taking an active role in facilitating fixed outcomes.

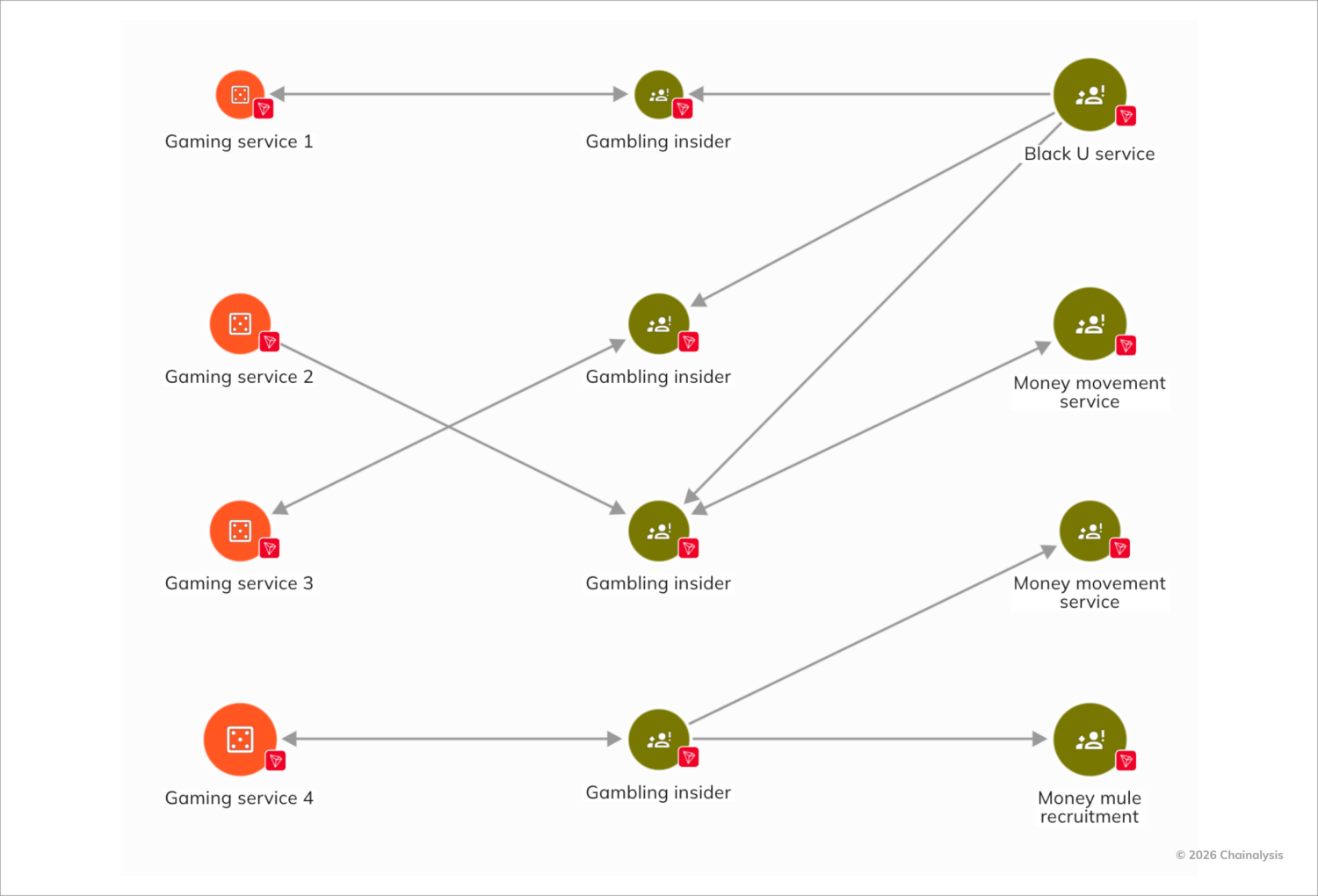

The Reactor graph below illustrates how gambling services can be used by insiders, where the insider extracts the fixed outcome proceeds from the gambling platform, then continues the laundering process by sending onward through additional money laundering services, such as Black U services and money mules. On-chain activity indicates the gambling insider operators send funds back into the gambling platforms as well.

6. Money movement services: mixing and swapping-as-a-service

Fund mixing to obfuscate transaction origins is well-established in sophisticated cyber heists. Professional mixing services, including Tornado Cash and Blender.io, earned international notoriety when they were sanctioned by the US government for their role in laundering stolen funds, with Tornado Cash later being de-listed by OFAC.

Within Southeast Asia’s underground banking ecosystem, specialized vendors across guarantee service platforms offer swapping-as-a-service to enable clients to convert their crypto into multiple assets. These swap services have found regional footing, especially among illicit actors active in Southeast Asia, China, and even North Korea, providing a laundering mechanism for those seeking to keep funds on-chain.

On-chain data reveals CMLN financial flows resemble traditional money laundering phases

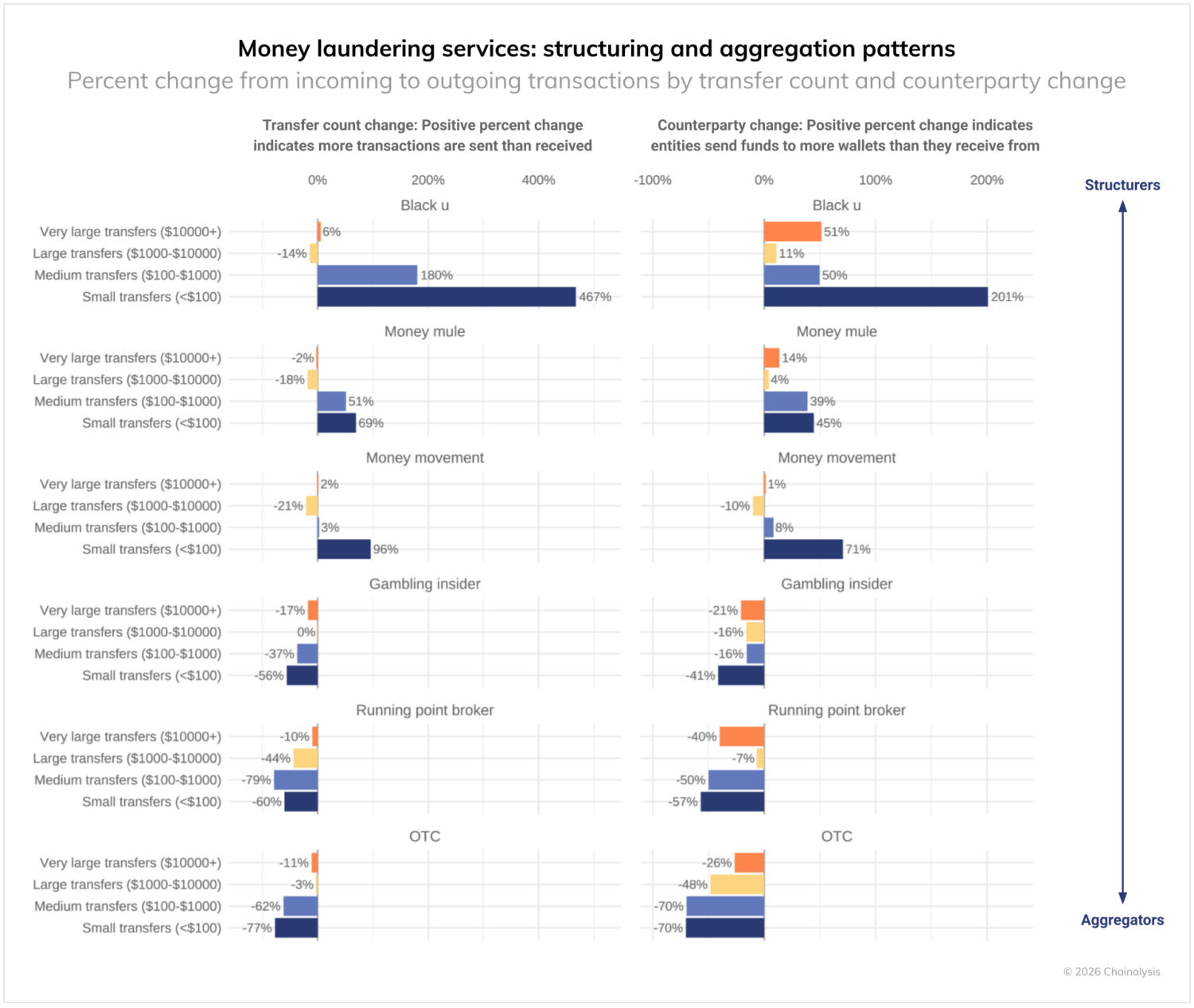

Analysis of transaction flows through CMLN services exposes industrial-scale deployment of traditional money laundering methodologies. The following chart tracks how different services fragment and consolidate illicit funds, revealing clear patterns of “structuring” (smurfing) and “aggregation” as funds move through the laundering cycle.

This quantitative framework can help identify services and their roles within the broader money laundering ecosystem, potentially even when an entity’s true operating mechanism is not yet known.

Black U services epitomize aggressive structuring behavior, with small (<$100) and medium ($100-$1000) transactions increasing by 467% and 180% respectively from inflow to outflow. These services also consistently fragment funds across more wallets, with very large transfers (>$10K) reaching 51% more destination wallets than source wallets. Money mules and money movement services, to a lesser but still significant degree, act likewise. In these cases, the shift toward smaller transactions and more counterparties represents textbook smurfing: breaking down large criminal proceeds to evade detection thresholds.

Gambling insiders, running point brokers, and OTC services operate as the ecosystem’s primary aggregators. For these services, incoming transfers across almost all denominations exceed outgoing transactions, suggesting these services pool funds from multiple points and send them out in bulk batches to fewer counterparty wallets on-chain. For the OTC services in particular, this consolidation pattern reflects their role in the integration phase — collecting numerous small deposits into wholesale amounts suitable for reintroduction into legitimate financial systems.

CMLNs prioritize VIP customers; most illicit funds are moved in minutes

The speed at which funds move through the different laundering services also reveal distinct patterns. In the charts below, we see that regardless of the laundering typology, high value transfers are prioritized. However, the services that build automated laundering mechanisms tend to become more efficient across any transfer value amount with time. Those that rely on manual mechanisms still tend to prioritize higher value transfers, but are less efficient at moving smaller transfers.

Black U services show the highest efficiency when it comes to processing funds, with very large transactions cleared on average in 1.6 mins in Q4 2025. The operational imperative to move illicit funds rapidly is likely a major contributing factor shaping the technical infrastructure of Black U services. In several of these services, self-service swapping mechanisms are also available. Customers simply provide their desired exchange amount and destination address, and the system executes the swap automatically. This automation serves a dual purpose: accelerating the laundering process while minimizing operational overhead and reducing the digital footprint that manual processing creates.

Similarly, gambling operations use integrated payment solutions to process substantial daily transaction volumes. These automated systems enable these platforms to handle large-scale financial flows efficiently, with funds deposited and cleared rapidly.

In contrast, money mules and running points exhibit far less consistency in transaction clearing patterns. These networks remain predominantly manual, requiring recruited individuals to actively process transactions in real-time using their personal bank accounts or digital wallets. This human element introduces variability into the laundering process, creating timing variations that differ from the consistent processing signatures of automated services.

Combating crypto-integrated laundering networks through public-private collaboration

Chinese-language guarantee platforms, money movement services, and associated financial crime networks reveal a complex and resilient ecosystem that continues to adapt despite enforcement efforts. As with other genres of illicit on-chain activity, actions against guarantee services can be disruptive, but the core networks persist and migrate to alternative channels when challenged.

The scale and integration of these operations present significant challenges for financial crime compliance, intelligence, and law enforcement efforts. Effective disruption requires targeting the illicit operators and vendors themselves, in addition to their advertising venues. These networks form the critical infrastructure enabling the conversion of illicit proceeds from fraud, scams, and other criminal activities into seemingly legitimate assets at scale.

More importantly, while CMLNs play an outsized role in crypto-enabled money laundering, they are not the only laundering networks to have adapted technologically. In December 2024, the United Kingdom’s National Crime Agency (NCA) disrupted a multi-billion dollar Russian-language money laundering network which provided services to a wide range of illicit actors, including Russian and international elites, cybercriminals, and drug gangs. As Keatinge noted, “There is a chasm in most countries between the capabilities of criminals and law enforcement when it comes to crypto use. A combination of nationally-based laws, barriers created by borders, poor information sharing, and limited crypto tracing and asset recovery capabilities mean that crypto offers criminals a low risk/high reward method of benefiting from their criminality. Whilst blockchain tracing companies have provided welcome assistance in some cases, this capacity building is just the tip of the iceberg. A systemic global effort to upskill the crypto capabilities of law enforcement around the world and create better information sharing mechanisms is urgently needed.”

Addressing the challenge of crypto-integrated laundering networks demands coordinated public-private partnership and a paradigm shift from reactive enforcement against individual platforms toward proactive disruption of underlying networks. Urben emphasized that “the most effective investigative strategy is to match your investigative tools against the operational approach of the CMLOs. To detect these money laundering networks, you need to rely on open source and human source intelligence combined with blockchain analysis. Only when these tools work together, and develop leads that feed into each other, will you be able to match the players to the currency movements and map the networks.”

By combining law enforcement’s legal authorities with the private sector’s technical capabilities and blockchain analytics expertise, the industry can more effectively identify and dismantle these services operating across multiple platforms, jurisdictions, and communication channels. On-chain transparency provides unprecedented visibility into these operations — when paired with cross-platform intelligence sharing and coordinated enforcement actions, these tools enable stakeholders to increase the cost and risk of operating large-scale money laundering services. Future intervention strategies must prioritize this collaborative approach to achieve meaningful, lasting disruption of crypto-integrated laundering networks, including CMLN operations.

[1] This is a lower bound estimate based on CMLN activities; it only reflects services attributed by Chainalysis and does not include Guarantee Services.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.