As with all new technologies, malicious actors have found ways to exploit cryptocurrency, despite its transparency and traceability. These actors presumably believe that crypto’s benefits — namely, the ability to transact instantaneously and across borders — outweigh the heightened risks of law enforcement detection. The most obvious examples are ransomware and darknet markets, which are inherently and deeply tied to cryptocurrency in that they more or less require crypto payments’ unique lack of middlemen in order to exist. However, as cryptocurrency grows and becomes more entwined with the world economy, we’re seeing it crop up in all forms of crime — even those that aren’t “crypto native” or even, in some cases, thought of as related to cybercrime, such as with conventional drug trafficking.

One example of this is cryptocurrency’s role in improper intellectual property (IP) use. Many illicit actors now accept crypto in exchange for IP-infringing products and services, such as pirated movies and infringing prescription medications, causing significant harm to the brands of authentic companies and their consumers.

Below, we’ll explore how crypto may be facilitating IP infringement in the entertainment industry and pharmaceutical industries, and how law enforcement can monitor on-chain transactions executed by the operators of these offending websites.

Cryptocurrency’s role in illicit streaming services

Over the past few years, streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ have attracted audiences from around the world due to the creation of regular, original content. When the streaming service model emerged, it opened access to hundreds — if not thousands — of movies and television shows for a small monthly fee. Consequently, many entertainment companies assumed it would reduce piracy and improve branding through stronger IP protection. Unfortunately, piracy is still common due to the ease of downloading and viewing videos on offending websites, and has led to substantial losses for legitimate entertainment companies.

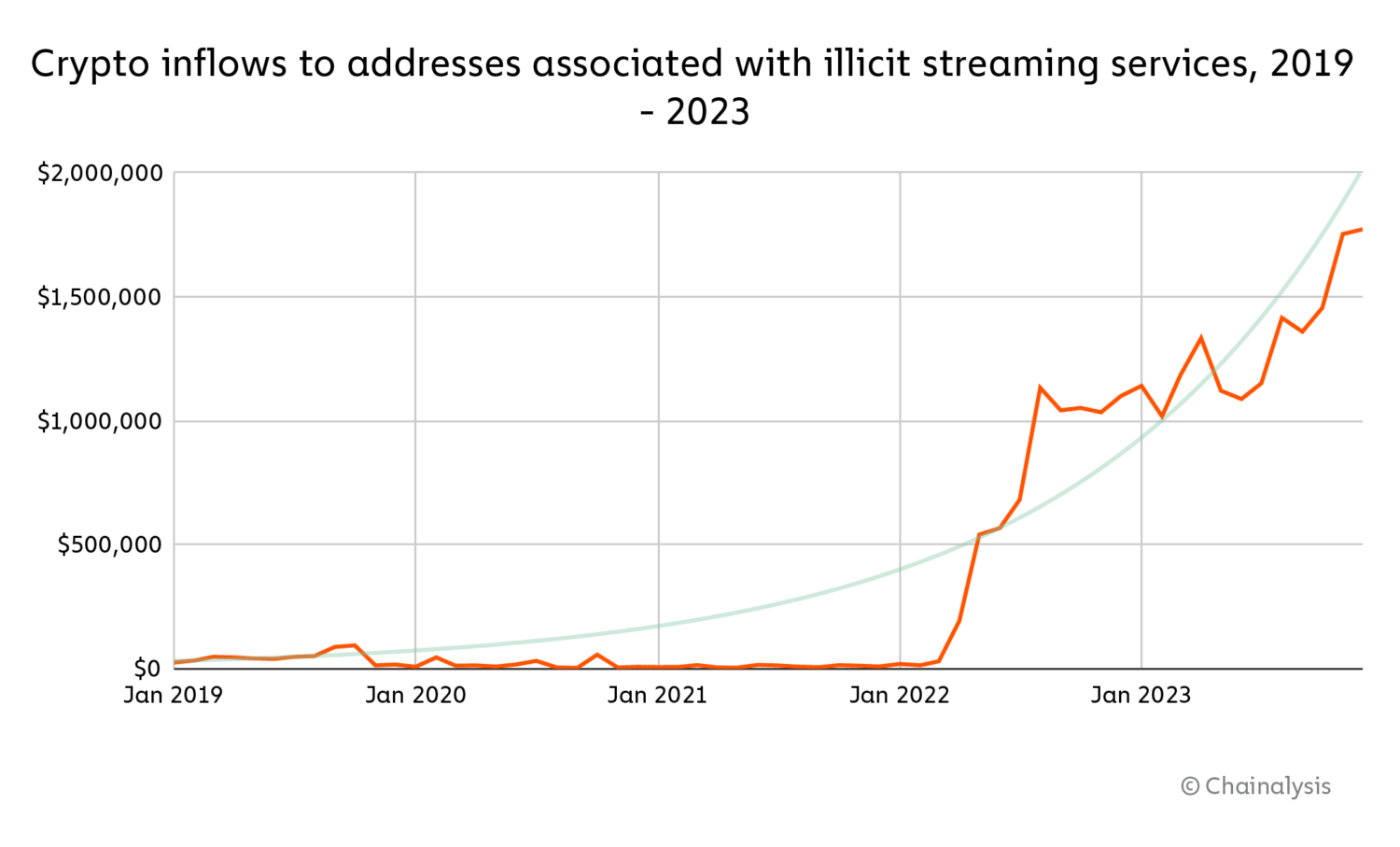

Nordic Content Protection (NCP), a television anti-piracy non-profit and one of our partners, has been monitoring streaming piracy to determine its global scale and how law enforcement can help protect legitimate content. NCP provided us with hundreds of crypto addresses they unearthed during their investigations into illicit streaming. We analyzed the activities of these addresses, in addition to those of illicit streaming addresses we already had, and determined that total inflows were approximately $24 million between 2019 and 2023.

Michael Lund, Security Manager of NCP, suspects that this activity extends far beyond the addresses provided and Europe in general. “Television piracy is a global challenge and a significant threat in Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and the Americas,” he explained. “We estimate that the number of users of illicit streaming services is in the hundreds of millions, leading to billions in lost revenue for legitimate services. This, in effect, leads to less tax revenue, fewer jobs, and poorer quality of content.” Indeed, a report by the Audiovisual Anti-Piracy Alliance (AAPA) revealed that legal Pay-T.V. providers in Europe lost €3.21 billion in revenue in 2021 to illegal IPTV, an illegitimate “industry” that includes several providers of illicit streaming to an estimated 17 million subscribers across Europe.

Lund added that many individuals and groups involved in IP infringement may also be involved in other serious crimes, such as organized money laundering. “In money laundering cases, we have seen that illicit revenue generated from the sale of illegal IPTV has been laundered through fake online hosting and IT services companies and through the purchase of fast food restaurants and traditional investments in real estate development.”

Many malicious actors accept crypto for counterfeit medical products listed on illicit pharmaceutical shop websites

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 50% of drugs sold on online pharmacies are counterfeit. Typically, organized criminal groups acquire and package illicit medicines and then list them on online pharmaceutical shops. These products appear to be legitimate prescription medications, thus infringing on trademarks and other IP of major pharmaceutical companies, and enabling illicit actors to target unsuspecting customers and reap financial rewards.

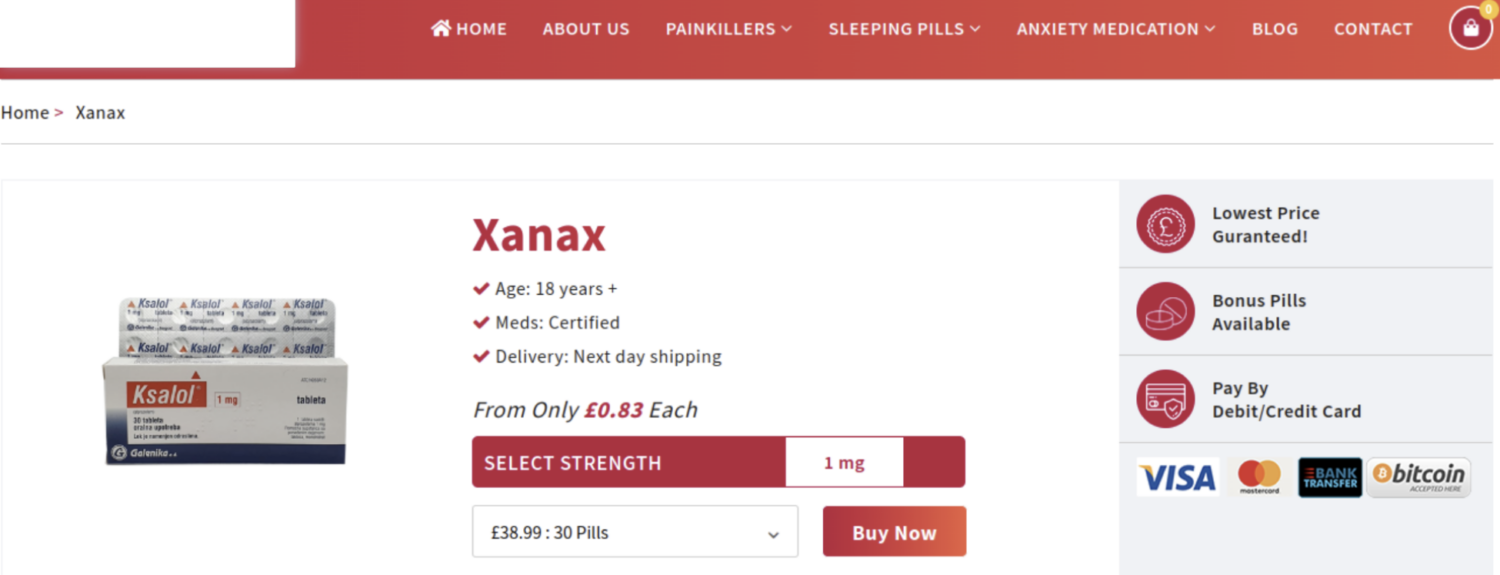

Many pharmaceutical shops complicit in the sales of counterfeit medicines accept payment in fiat, whereas some accept both fiat and crypto, as shown in the screenshot below of a merchant accepting Bitcoin.

In many cases, it is unclear whether pharmaceutical shops like the one above are selling legitimate products diverted from the legal supply chain or generic medical products branded as legitimate. Regardless, actors selling these products in exchange for crypto are harming the IP rights of legitimate pharmaceutical companies.

So, how can law enforcement and IP owners monitor this activity? The case study below illustrates one way on-chain analysis can be used to retrace the steps of those operating crypto addresses associated with these pharmaceutical shops.

Case study: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)

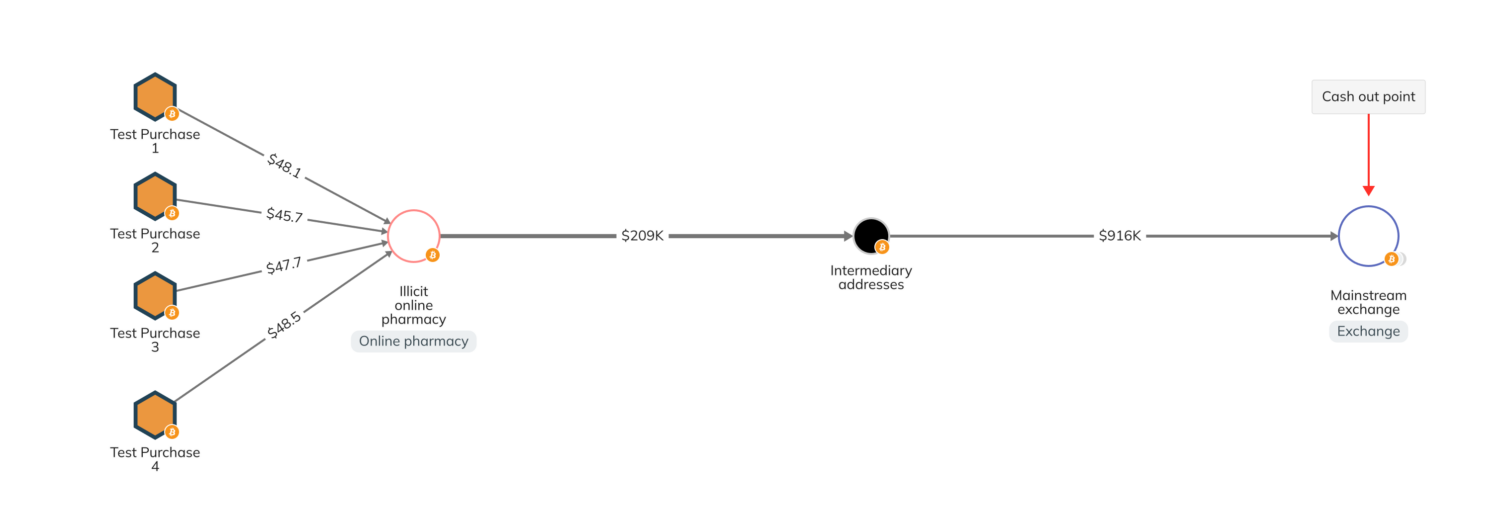

The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is an organization based in the United Kingdom, committed to maintaining safety of medicines and medical devices. Due to the increase of illicit pharmaceutical shops accepting crypto, MHRA has been closely monitoring the on-chain activity of certain shops, often by executing test transactions to establish the typical flow of funds after customers make purchases.

The following Chainalysis Reactor graph illustrates an example of what these test transactions look like on-chain. On the left, MHRA made four test purchases in crypto related to counterfeit medical products sold on an online pharmaceutical shop — this provided them with addresses operated by the actors running the shop. Once these actors received MHRA’s payments, they transferred the funds to several intermediary addresses. Eventually, the funds reached a mainstream exchange, which likely represents the cash-out point for the operator of the online pharmacy. The intermediary addresses also received funds from addresses that behave in the same fashion as MHRA’s target and are likely other services that are a part of the same malicious group.

Upon completion of these test transactions, MHRA discovered that the actors had transferred millions of dollars to the same mainstream exchange, some — but not all — of which likely came from the sale of illicit medicines. MHRA then conducted inquiries with the exchange, learning that a small portion of the transferred funds was still held at the exchange. MHRA concluded by freezing the funds and sharing information with additional regulatory agencies.

Monitoring on-chain activity across all industries

Our exploration of crypto and IP infringement illustrate how crypto is becoming a part of the financial infrastructure for many different types of illicit activities. Fortunately, companies in any industry may be able to leverage technologies that monitor on-chain activity, such as Chainalysis’s product suite, to determine the extent of IP infringement facilitated by crypto and whether this activity is also linked to other suspicious conduct.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.