The use of cryptocurrency by terrorist organizations represents a small share of illicit transactions in the cryptocurrency ecosystem, but it is an ever-present concern. At the same time, the inherent transparency and traceability of blockchain technology makes crypto a less favorable vehicle for terrorism financing.

The gravity of any funds contributing to terrorism, regardless of the amount, requires the utmost attention from the public and private sectors. The challenge of validating terror related activities in both fiat and cryptocurrency complicates efforts to draw clear estimates on overall volumes. Misinterpretation of crypto transaction data may result in unnecessary de-risking on the one hand, or non-compliance and increased risk of facilitating terrorism financing on the other. Furthermore, analyzing the flow of funds in this nuanced ecosystem without proper context can lead to inaccurate conclusions about the true scale of terrorism financing.

The situation is further complicated when considering the necessity of humanitarian aid in many jurisdictions that also present terrorism financing risk, primarily those in ongoing states of war. There’s an ethical dilemma in potentially blocking legitimate humanitarian aid in efforts to curb terror financing. Blanket labeling of transactions as terrorist activities by private entities who lack the authority to make such designations can have far-reaching implications. A multifaceted approach incorporating not only intelligence, but also regulatory and ethical considerations with a commitment to factual accuracy and thorough verification is essential.

How terrorist organizations have used cryptocurrency

In this analysis of on-chain terrorism financing, we will focus on two primary mechanisms: complex organizational-level financial facilitation and small crowdfunding campaigns.

First, we look at groups like Hezbollah, known for their complex networks in traditional finance and their efforts to extend these operations with cryptocurrency. We review on-chain activity associated with Hezbollah, including their reliance on service providers and engagement with mainstream exchanges. Then, we examine a second, less sustainable method: crowdfunding, where terrorist organizations have only achieved limited success.

Exploring the financial networks of complex terrorist organizations

In June 2023, Israel’s National Bureau for Counter Terror Financing (NBCTF) announced the first ever seizure of cryptocurrency linked to Hezbollah and Iran’s Quds Force. This seizure, totaling about $1.7 million, targeted financial facilitator Tawfiq Muhammad Said Al-Law and the crypto wallet network he utilized to facilitate his activity. Al-Law is a Syria-based hawala operator who was involved in running Hezbollah’s cryptocurrency infrastructure along with sanctioned senior Hezbollah members.

The NBCTF seizure provides a unique look at Hezbollah’s cryptocurrency financing infrastructure, which uses a mix of service providers and mainstream exchanges, not unlike their traditional financial exploits. For groups like Hezbollah, service providers like money services businesses (MSBs) frequently emerge as key facilitators, processing financial transactions that exceed the scale of typical individual dealings but fall well below the activity of most cryptocurrency exchanges. These intermediaries vary widely in their operations, with some functioning similarly to over-the-counter (OTC) brokers, handling a significant volume of transactions. Others, like hawalas, operate on a smaller street-level scale.

The involvement of service providers that may facilitate illicit transactions introduces a significant obstacle. Calculating terrorism financing totals based on the flow of funds through these intermediary service providers significantly increases the risk of overestimating terrorism-related activities, as these services generally also process unrelated transactions carried out by everyday users with no illicit intent. A service that attracts illicit activity due to lax compliance practices would present a significantly different risk profile from one whose operators are actively facilitating on behalf of terrorist organizations or state sponsors of terror, like Iran. Although there are no confirmed on-chain instances of the latter case, that is not to say it cannot happen — it simply means they have not utilized known Iranian services to potentially facilitate this activity. Therefore, government agencies with access to off-chain intelligence are more likely to detect these activities, and can leverage blockchain analysis tools to further investigate these financial flows.

Complex organizations like Hezbollah have historically leveraged facilitators like Al-Law, who are not necessarily on sanctions lists or did not have clear open affiliation with Hezbollah, which makes it difficult for financial institutions and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) to effectively flag risks in both traditional finance and cryptocurrency. Their deliberate attempts to evade detection and sanctions mean that mainstream and regional service providers may inadvertently become exposed to these illicit networks.

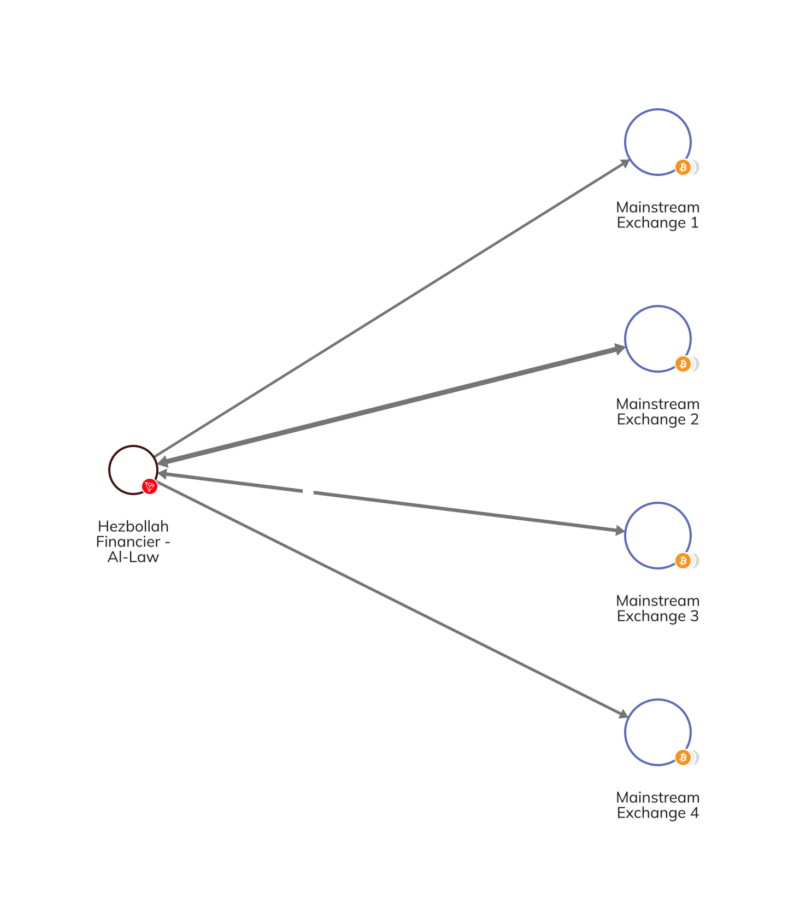

Al-Law used a network of legitimate mainstream exchanges, as well as other service providers, to facilitate the movement of his funds. Out of 904 total transfers made by the known Al-Law wallet in just under one year, 145 involved mainstream exchanges.

We can see some of this activity on-chain in the Chainalysis Reactor graph below.

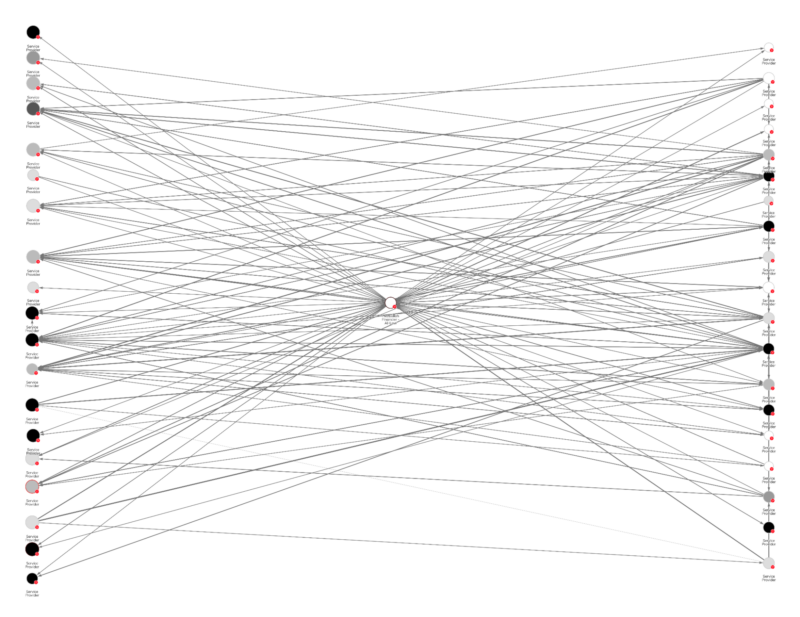

Al-Law also employed an extensive network of wallets beyond mainstream exchanges for cryptocurrency transactions. These wallets collectively received funds ranging from millions to over $1 billion in cryptocurrency, involving hundreds to tens of thousands of transfers separate from those with Al-Law. This suggests the potential involvement of service providers. Whether these service providers are aware or not, their involvement in terrorist financing activities can contribute to a complex web used by terrorist organizations to deliberately conceal the source, destination, and purpose of the transactions.

The Chainalysis Reactor graph below highlights Al-Law’s usage of a complex network of potential service providers:

Financially astute terrorist organizations may attempt to leverage more intricate networks to evade detection. This includes the use of OTCs, hawalas, smaller informal exchanges, and even mainstream services. The transparent nature of public blockchains, combined with blockchain analysis tools, can provide unparalleled insights into the on-chain activity of major terrorism networks. When terrorists use cryptocurrency, transactions are traceable across public ledgers, making it possible to follow the flow of funds with a level of detail not typically available with traditional financial avenues. Investigators can decipher and map the intricate financial maneuvers of these organizations, identifying tactics of crypto movement and management.

How small-scale crowdfunding campaigns subsidize terror activity

Public donation campaigns are less sophisticated than the elaborate financial networks of some terrorist groups. These campaigns are typically run under the guise of charities or crowdfunding, which have generally proven to be less effective over time. The public nature of these efforts, paired with the transparency and immutability of the blockchain, make social media campaigns for known terrorist organizations a challenging fundraising method. Last year, Al-Qassam Brigades (AQB), the military wing of Hamas, announced their decision to stop accepting crypto donations, due to the risk of prosecution for potential donors.

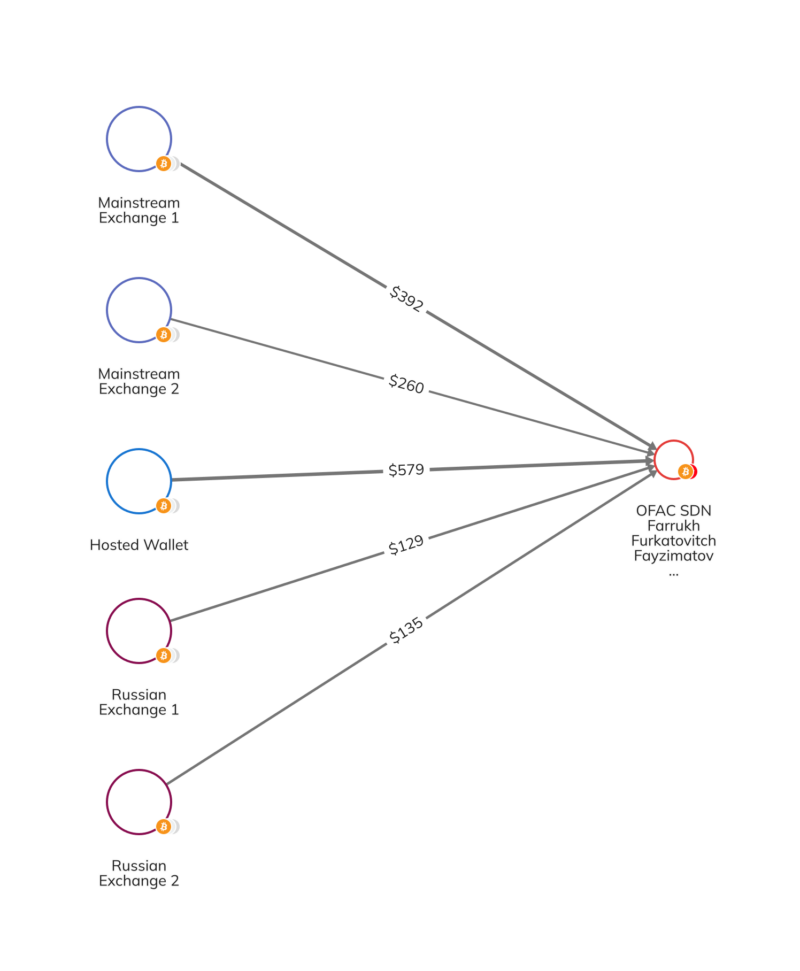

Despite these obstacles, terrorist organizations continue to turn to social media to solicit donations. Consider the case of Farrukh Furkatovitch Fayzimatov, a Tajik national and Syria-based fundraiser and recruiter for Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) — a designated terrorist organization. The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned Fayzimatov in 2021 for using social media to disperse propaganda and solicit donations on behalf of HTS, which included a specific bitcoin address in this designation. Nevertheless, Fayzimatov continues to create new crypto addresses in various currencies since his designation, amassing over $12,000 from various counterparts. These funds include small contributions from mainstream exchanges, hosted wallets, and even Russian exchanges without Know Your Customer (KYC) processes.

We can see some of this activity on the Chainalysis Reactor graph below.

The case of Fayzimatov is more clear-cut due to his official sanctions designation, but distinguishing between terror financing and legitimate humanitarian efforts is often challenging, particularly in war-torn regions. To help address this, OFAC issued an advisory clarifying the provision of permissible humanitarian support to Syria in August of 2023. A risk remains, however, that terrorist organizations might exploit the nuance of general licenses to raise funds under the veil of legitimate charity.

Chainalysis has observed efforts by militant and pro-ISIS social media accounts to raise funds, including via cryptocurrency. These fundraising campaigns frequently purport to be gathering humanitarian aid, often focusing on the well-known al-Hol and al-Roj detainment camps. They emphasize the plight of imprisoned women and children, leveraging narratives of neglect, abuse, and poor conditions in these camps to gain legitimacy and bolster fundraising. Cases such as these, in which legitimate humanitarian concerns mesh with extreme ideology and lack of accountability as to the ultimate destination of all funds raised, present significant analytic and ethical quandaries.

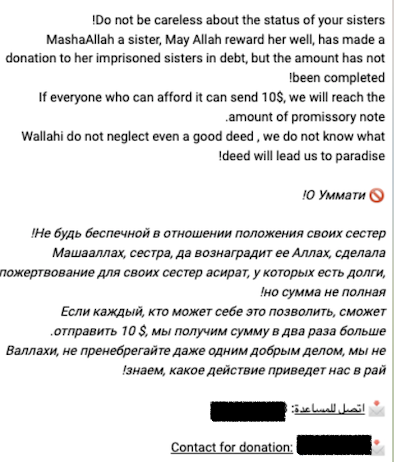

Some of the al-Hol and al-Roj fundraising channels are fairly circumspect regarding their ideology, focusing entirely on daily life in the camps and humanitarian needs. Below is a machine translation of an example fundraising post:

However, other donation channels are more explicit regarding their ideology and show higher levels of operational security, including fundraising campaigns in which prospective donors must contact the channel administrator directly. The below post from a separate donation channel shows concerning imagery (left), with text evoking the ISIS flag (right):

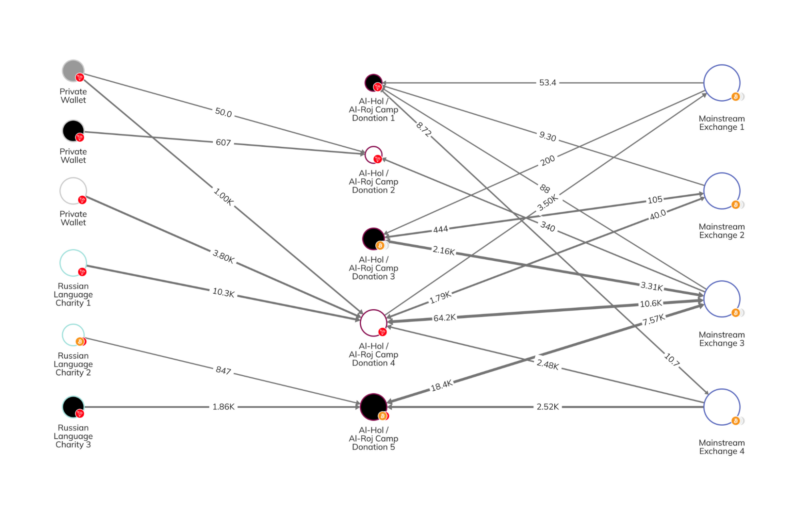

As seen in the Chainalysis Reactor graph below, al-Hol and al-Roj camp crypto donation campaigns are becoming more commonplace, receiving funds from a variety of sources including mainstream exchanges, Russian language charities, and other private wallets.

Distinguishing between legitimate humanitarian aid and terrorist financing becomes increasingly difficult for the private sector, especially when considering the analysis to make a decision of whether to block funds and de-risk, or to allow the transfer, based solely on details from social media donation campaigns. These social media accounts often have minimal identifying information about the operator or ultimate use of all funds raised.

The challenge lies in distinguishing legitimate humanitarian aid, such as fundraising for disasters like the Syria/Turkey earthquakes last year, and fundraising that might inadvertently support terrorism-related activities. Monitoring these broad donation networks to ensure funds are used appropriately is difficult, underscoring the risk of mistakenly labeling all such contributions as terrorism related, which could hinder much-needed humanitarian aid. In response, OFAC issued another compliance advisory in November of 2023 to provide guidance around the provision of aid to the Palestinian people, similar to the one issued for Syria. This issue has gained urgency as the conflict between Israel and Hamas intensifies, balancing dire humanitarian needs against the risks of terror financing.

The difficulties of identifying and combating complex terrorism financing networks on-chain are both intricate and high-stakes. How does one define the line between legitimate financial transactions and those that are tied to terrorism? Who holds the authority to draw this crucial line, and how do we account for the nuances that often blur it?

Collaboration between the private and public sectors to combat terrorism financing

Contrary to common belief, cryptocurrency is not a widely used or effective tool for terrorism funding due to its transparency, traceability, and immutability. Nonetheless, even small amounts of funds sent to terrorists can have devastating consequences.

Public-private partnerships play a fundamental role in identifying, analyzing, and validating potential terrorist financing risks. Absent this collaboration, private sector firms struggle to make informed, risk-based decisions, which could result in either mistakenly blocking legitimate funds or inadvertently allowing funds to reach the hands of terrorists. Bridging this gap requires cooperation between public and private sectors, with financial institutions, exchanges, and blockchain analytics companies contributing to lead generation and insight sharing. Additionally, the public sector’s communication around campaigns with potential terrorist financing risks is critical. Such cooperation ensures that the financial ecosystem does not inadvertently support terrorism, while also facilitating the flow of legitimate, critical humanitarian aid to its intended recipients.

These efforts have already resulted in the seizure of funds from groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, demonstrating that it is possible to deconstruct and disrupt financial infrastructure supporting terrorism. However, identifying terrorism financing on the blockchain is a complex, high-stakes task that requires a nuanced approach, clear delineation, and ongoing collaboration between the public and private sectors.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.