Cybercriminals looking to launder money are often drawn to cryptocurrency due to its near-instant, pseudonymous, and cross-border capabilities. In 2022 alone, Chainalysis tracked a total of $23.8 billion worth of crypto laundered by cybercriminals, but keep in mind that this figure only includes funds associated with addresses tied to forms of crime that are inherently related to cryptocurrency, like ransomware, exchange hacks, and crypto scams. For the most part, it doesn’t include cases in which cryptocurrency is used to launder money made from crimes that took place “off-chain.”

There’s no way to track this type of activity at scale, since the funds in question are simply moving through cryptocurrency addresses that otherwise look legitimate. However, we know that this activity occurs, and investigators can use our tools to trace the flow of these funds. Further, when our customers alert us to this activity and provide the addresses and transactions involved, we can label those addresses and track the funds just as we would in any other case.

That’s exactly what happened recently with a large, Japan-based cryptocurrency exchange that uses Chainalysis. Police alerted the exchange that one of its users had deposited fiat currency derived from fraudulent activity and converted it into cryptocurrency in order to launder it. In this blog, we’ll show you what their money laundering strategy looked like on-chain, and help you understand how exchanges can respond effectively when their platforms are abused by criminals.

Suspected on-chain Japanese money laundering activities

Our knowledge of this suspicious activity began when our exchange customer relayed to us law enforcement’s assessment that the fraudulent accounts were being used to launder funds derived from scamming. Although we don’t know the nature of the fraud in question, it’s possible that it involves a financial scam, as these have been a huge problem in Japan recently. For instance, news publications have detailed occurrences of bank impersonation, insurance fraud, and even job postings for part-time criminal work across the country.

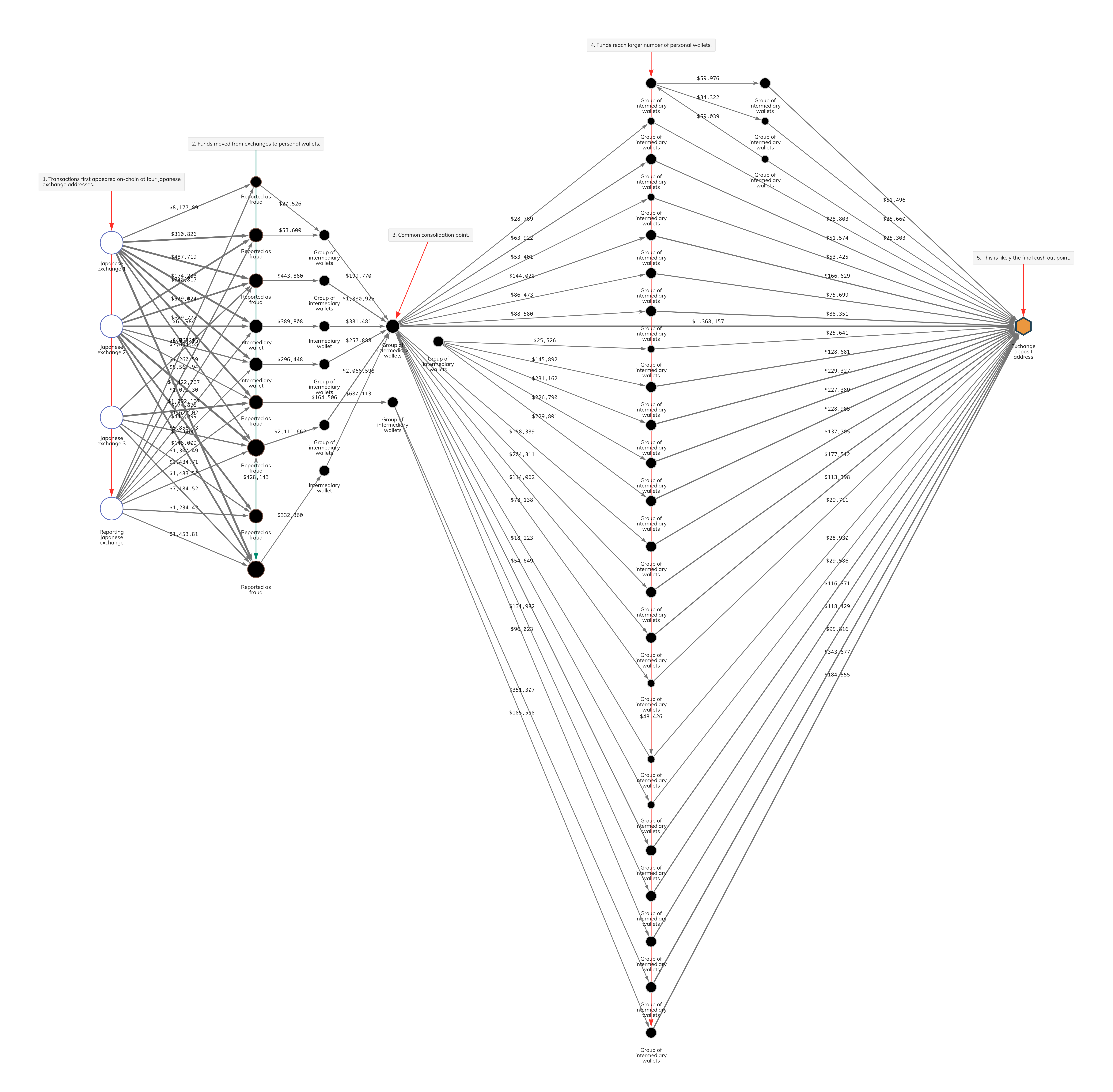

The criminals involved in this case converted ill-gotten fiat into cryptocurrency, then sent it through a series of personal wallets, and eventually to a new exchange where it could be converted into cash that would appear legitimate. We can see this activity on the Chainalysis Reactor graph below.

In the top left corner of the graph, we see funds moving from the reporting exchange to a group of personal wallets, reminiscent of both the “placement” and “layering” stages of money laundering. These are the transactions that were provided to us by the exchange, and were initiated by the fraudulent accounts in question. We had previously identified many of the personal wallets receiving that first round of transactions as being associated with scams, which allowed us to identify and alert other Japan-based exchanges whose users had also sent funds to those wallets.

Once the funds moved from the initial exchanges and were spread across several intermediary wallets (steps 1 and 2 on our Reactor graph; more layering), the funds were then reconsolidated in a single personal wallet (step 3). We know from previous cases that this pattern of diffusing funds across many wallets and reconsolidating them in a single wallet is a common money laundering tactic. From there, the funds were once again sent and spread across an even larger number of personal wallets (step 4; more layering), and then reconsolidated again at a single deposit address at a mainstream exchange, likely to be cashed out (step 5 in what’s known as the “integration” stage of money laundering).

The establishment of fraudulent exchange accounts for money laundering purposes is nothing new. In the case of Japan, a major online bank recently implemented a restriction to prevent this whereby new account holders are not allowed to send Yen to crypto exchanges within one month of opening accounts. Additionally, the Japan Cybercrime Control Center (JC3) recently published guidance for industries and law enforcement about how to better identify and mitigate these types of online crimes.

The future of collaboration between police, banks, and exchanges

The above example illustrates strong cooperation between the police, banks, crypto exchanges, and Chainalysis. In the future, collaboration between different organizations will be essential for combatting crypto-related crimes, whether they originate off-chain or on-chain. We hope to facilitate this by providing necessary parties with access to relevant data and consistently innovating to improve our product suite.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making these types of decisions. Chainalysis has no responsibility or liability for any decision made or any other acts or omissions in connection with Recipient’s use of this material.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.