This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!

Cybercriminals dealing in cryptocurrency share one common goal: Move their ill-gotten funds to a service where they can be kept safe from the authorities and eventually converted to cash. That’s why money laundering underpins all other forms of cryptocurrency-based crime. If there’s no way to access the funds, there’s no incentive to commit crimes involving cryptocurrency in the first place.

Money laundering activity in cryptocurrency is also heavily concentrated. While billions of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency moves from illicit addresses every year, most of it ends up at a surprisingly small group of services, many of which appear purpose-built for money laundering based on their transaction histories. Law enforcement can strike a huge blow against cryptocurrency-based crime and significantly hamper criminals’ ability to access their digital assets by disrupting these services. We saw an example of this last year, when the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctioned two of the worst-offending money laundering services — Suex and Chatex — for accepting funds from ransomware operators, scammers, and other cybercriminals. But as we’ll explore below, many other money laundering services remain active.

2021 cryptocurrency money laundering activity summarized

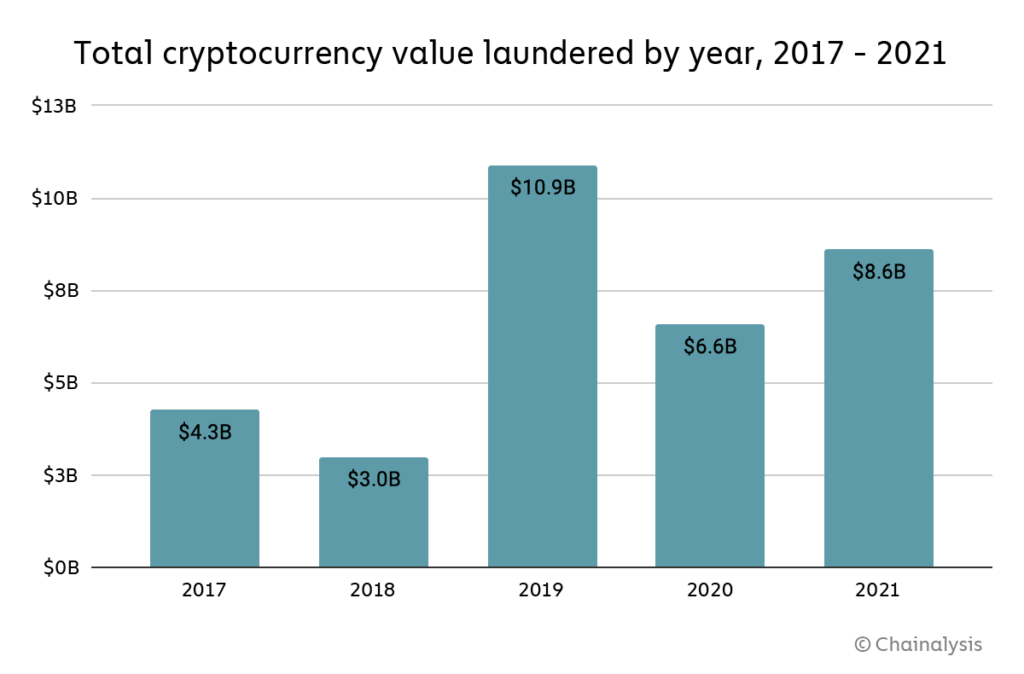

Overall, going by the amount of cryptocurrency sent from illicit addresses to addresses hosted by services, cybercriminals laundered $8.6 billion worth of cryptocurrency in 2021.

That represents a 30% increase in money laundering activity over 2020, though such an increase is unsurprising given the significant growth of both legitimate and illicit cryptocurrency activity in 2021. We also need to note that these numbers only account for funds derived from “cryptocurrency-native” crime, meaning cybercriminal activity such as darknet market sales or ransomware attacks in which profits are virtually always derived in cryptocurrency rather than fiat currency. It’s more difficult to measure how much fiat currency derived from offline crime — traditional drug trafficking, for example — is converted into cryptocurrency to be laundered. However, we know anecdotally this is happening, and later in this section provide a case study showing an example of it.

Overall, cybercriminals have laundered over $33 billion worth of cryptocurrency since 2017, with most of the total over time moving to centralized exchanges. For comparison, the UN Office of Drugs and Crime estimates that between $800 billion and $2 trillion of fiat currency is laundered each year — as much as 5% of global GDP. For comparison, money laundering accounted for just 0.05% of all cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2021. We cite those numbers not to try and minimize cryptocurrency’s crime-related issues, but rather to point out that money laundering is a plague on virtually all forms of economic value transfer, and to help law enforcement and compliance professionals be aware of just how much money laundering activity could theoretically move to cryptocurrency as adoption of the technology increases.

The biggest difference between fiat and cryptocurrency-based money laundering is that, due to the inherent transparency of blockchains, we can more easily trace how criminals move cryptocurrency between wallets and services in their efforts to convert their funds into cash. What kinds of cryptocurrency services do criminals rely on for this?

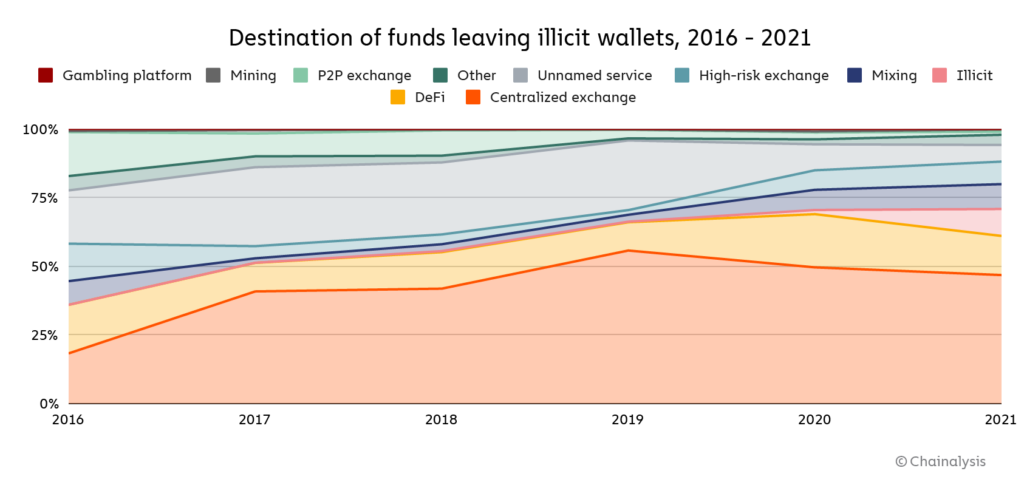

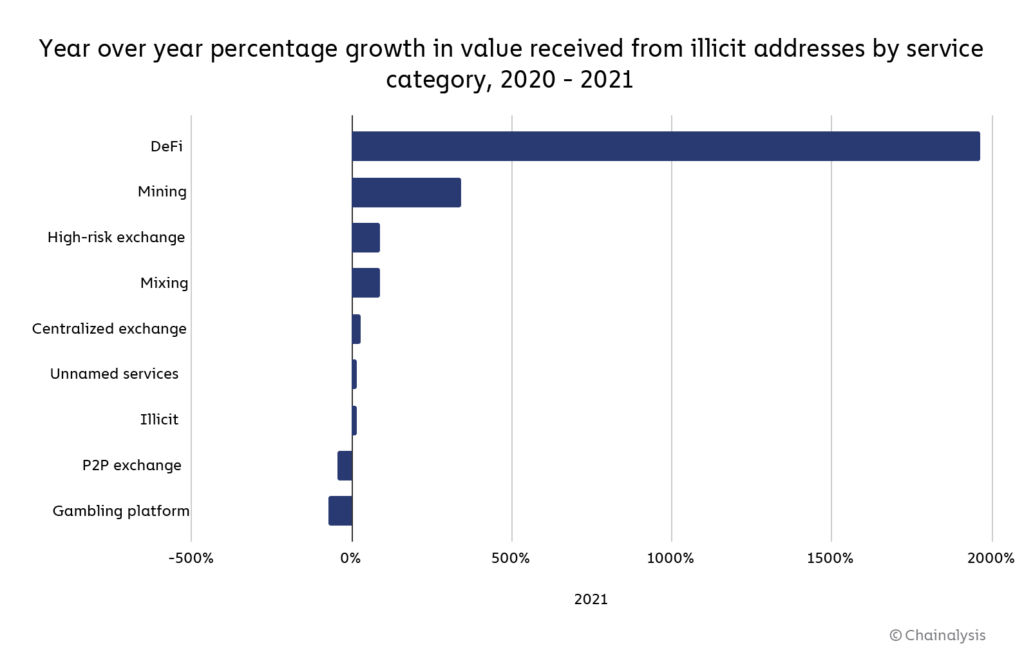

For the first time since 2018, centralized exchanges didn’t receive the majority of funds sent by illicit addresses last year, instead taking in just 47%. Where did cybercriminals send funds instead? DeFi protocols make up much of the difference. DeFi protocols received 17% of all funds sent from illicit wallets in 2021, up from 2% the previous year.

That translates to a 1,964% year-over-year increase in total value received by DeFi protocols from illicit addresses, reaching a total of $900 million in 2021. Mining pools, high-risk exchanges, and mixers also saw substantial increases in value received from illicit addresses as well.

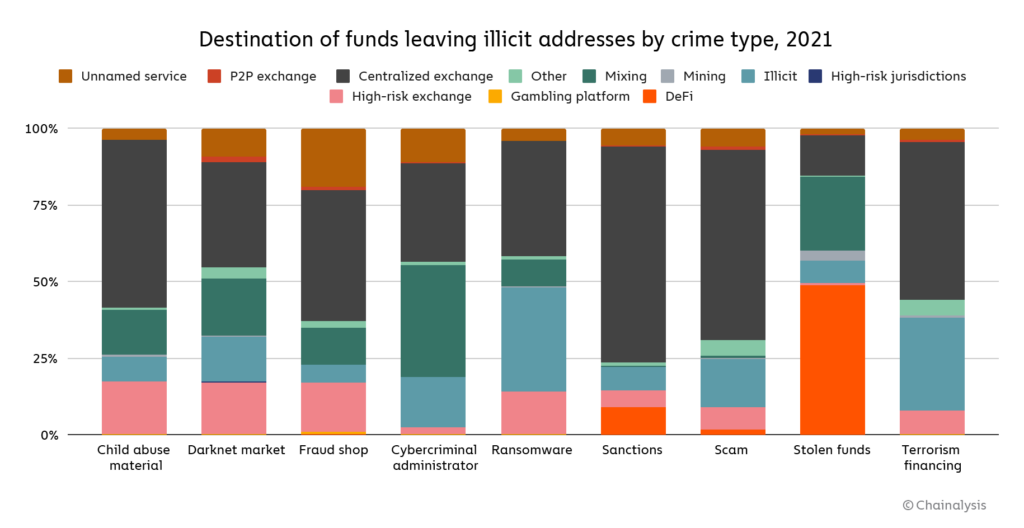

We also see patterns in which types of services different types of cybercriminals use to launder cryptocurrency.

One thing that stands out is the difference in laundering strategies between the two highest-grossing forms of cryptocurrency-based crime in 2021: Theft and scamming.

Addresses associated with theft sent just under half of their stolen funds to DeFi platforms — over $750 million worth of cryptocurrency in total. North Korea-affiliated hackers in particular, who were responsible for $400 million worth of cryptocurrency hacks last year, used DeFi protocols for money laundering quite a bit. This may be related to the fact that more cryptocurrency was stolen from DeFi protocols than any other type of platform last year. We also see a substantial amount of mixer usage in the laundering of stolen funds.

Scammers, on the other hand, send the majority of their funds to addresses at centralized exchanges. This may reflect scammers’ relative lack of sophistication. Hacking cryptocurrency platforms to steal funds takes more technical expertise than carrying out most scams we observe, so it makes sense that those cybercriminals would employ a more advanced money laundering strategy.

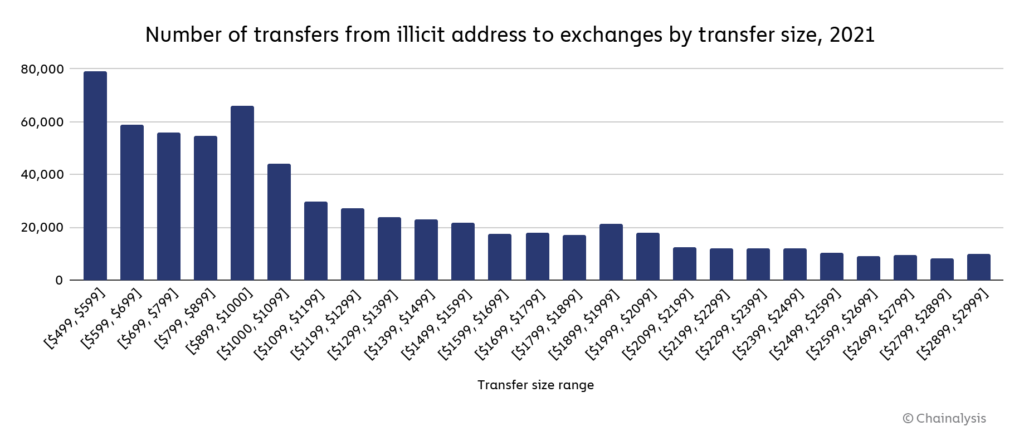

We also need to reiterate that we can’t track all money laundering activity by measuring the value sent from known criminal addresses. As stated above, some criminals use cryptocurrency to launder funds from crimes that happen offline, and there are many criminal addresses in use that have yet to be identified. However, we can account for some of these more obscured instances of money laundering by looking for transaction patterns suggesting that users were trying to avoid compliance screens. For instance, due to regulations like the Travel Rule, cryptocurrency businesses in many countries must conduct additional compliance checks, reporting, and information sharing related to transactions above $1,000 USD in value. As you might expect, illicit addresses send a disproportionate number of transfers to exchanges just below that $1,000 threshold.

Exchanges using Chainalysis would be able to see that these funds are coming from illicit addresses regardless of transfer size. But more generally, compliance teams should consider treating users who consistently send or receive transactions of that size with extra scrutiny. Repeated instances of transactions just below the threshold may indicate users are doing what’s known as structuring, meaning purposely breaking up large payments into smaller ones just below reporting thresholds in order to fool compliance teams.

Money laundering activity remains highly concentrated in 2021, but less so than in 2020

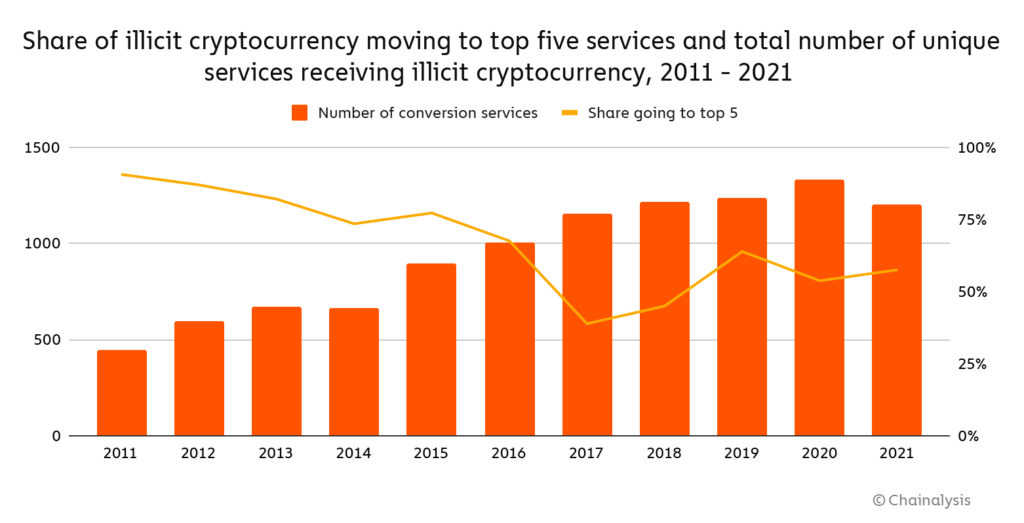

As we’ve discussed previously, money laundering activity is heavily concentrated to just a few services. We can see how that concentration has changed over time below.

With fewer services used in 2021, money laundering concentration initially appears to have increased slightly. 58% of all funds sent from illicit addresses moved to five services last year, compared to 54% in 2020.

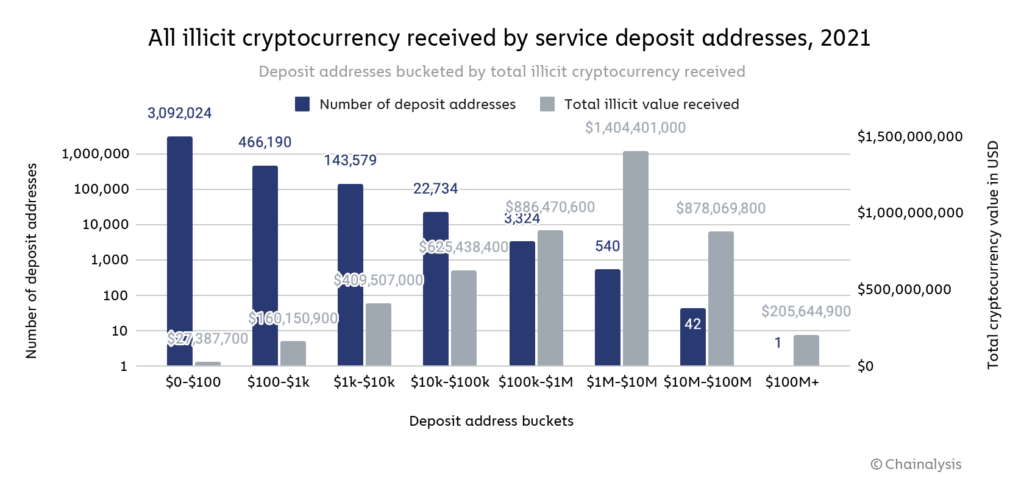

However, money laundering activity is better viewed at the deposit address level rather than the service level. The reason for that is that many of the money laundering services cybercriminals are nested services, meaning they operate using addresses hosted by larger services in order to tap into those larger services’ liquidity and trading pairs. Over-the-counter (OTC) brokers, for example, often function as nested services with addresses hosted by large exchanges. In the graph below, we look at all service deposit addresses that received any illicit funds in 2021, broken down by the range of illicit funds received.

How to read this graph: This graph shows service deposit addresses bucketed by how much total illicit cryptocurrency value each address received individually in 2021. Each blue bar represents the number of deposit addresses in the bucket, while each grey bar represents the total illicit cryptocurrency value received by all deposit addresses in the bucket. Using the first bucket as an example, we see that 3,092,024 deposit addresses received between $0 and $100 worth of illicit cryptocurrency, and together all of those deposit addresses received a total of $27.4 million worth of illicit cryptocurrency.

A group of just 583 deposit addresses received 54% of all funds sent from illicit addresses in 2021. Each of those 583 addresses received at least $1 million from illicit addresses, and in total they received just under $2.5 billion worth of cryptocurrency. An even smaller group of 45 addresses received 24% of all funds sent from illicit addresses for a total of just under $1.1 billion. One deposit address received just over $200 million, all from wallets associated with the Finiko Ponzi scheme.

While money laundering activity remains quite concentrated, it’s less so than in 2020. That year, 55% of all cryptocurrency sent from illicit addresses went to just 270 service deposit addresses. Law enforcement action could be one possible reason money laundering activity became less concentrated. As we mentioned above, last year OFAC sanctioned Suex, a Russia-based OTC broker, that had received tens of millions’ of dollars’ worth of cryptocurrency from addresses associated with ransomware, scams, and other forms of criminal activity. Soon after, OFAC also sanctioned Chatex, a P2P exchange founded by the same person as Suex with a similar client profile. While we couldn’t share their names at the time, addresses associated with both services appeared in the 270 we identified as the biggest laundering addresses in last year’s report.

It’s possible that some money laundering services ceased operations after seeing those and other actions taken against illicit platforms, forcing cybercriminals to disperse their money laundering activity to other operators. It’s also possible that money laundering services have continued to operate but spread their activity across more deposit addresses, which would contribute to the lessening concentration we see above.

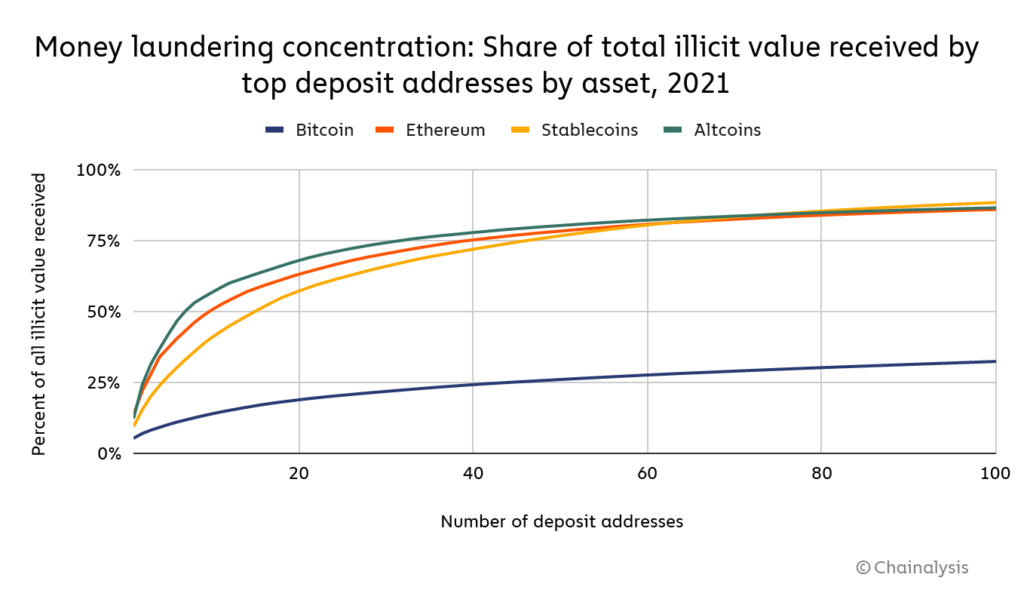

We also see differing levels of concentration in money laundering depending on the asset.

Bitcoin’s money laundering activity is the least concentrated by far. The 20 biggest money laundering deposit addresses receive just 19% of all Bitcoin sent from illicit addresses, compared to 57% for stablecoins, 63% for Ethereum, and 68% for altcoins.

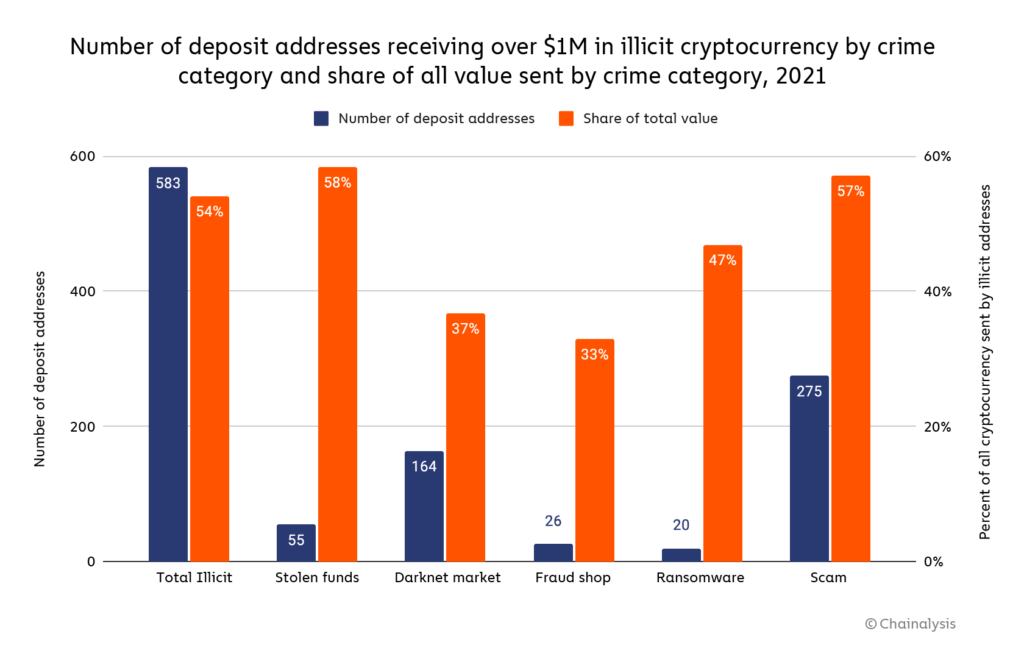

We also see differences in the level of money laundering concentration for different types of cybercriminals. The chart below breaks down by crime category all addresses that received over $1 million in illicit cryptocurrency in 2021, and the share of all funds sent from those criminal categories that the deposit addresses account for.

What stands out most is how much less concentrated money laundering activity is for scammers and darknet market vendors and administrators compared to other crime categories. This may reflect the fact that the criminal activity for those categories is itself less concentrated. Many more cybercriminals at varying levels of sophistication are participating in darknet market sales and scamming, so it makes sense we’d see those cybercriminals’ funds dispersed across more deposit addresses for money laundering — each player may follow their own strategy. For more sophisticated forms of cybercrime like ransomware, administrators at the biggest ransomware strains account for a greater share of all activity, so we’d expect to see their money laundering be more concentrated as well.

Case study: Spartan Protocol hacker uses DeFi protocols and chain hopping to launder stolen funds

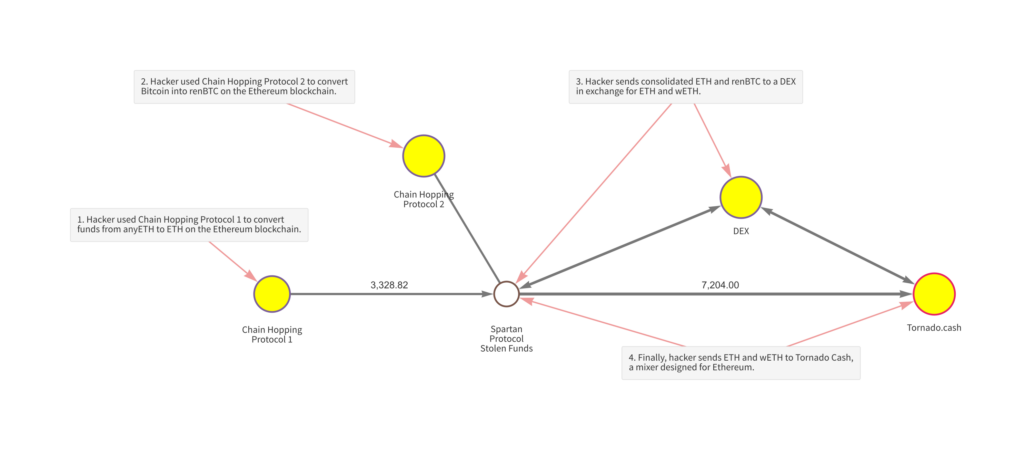

As we discussed above, usage of DeFi protocols for money laundering skyrocketed in 2021. The Spartan Protocol hack provides a good example of what this activity looks like.

In May 2021, one or more hackers exploited a code vulnerability to steal over $30 million worth of cryptocurrency from the protocol — mostly its native SPARTA token. The hacker then converted much of those funds into anyETH and anyBTC, which are Ethereum and Bitcoin composites respectively built on separate blockchains from those assets. Some of that anyBTC was then swapped for Bitcoin, thereby moving to the Bitcoin blockchain, which brings us to the transactions seen on the Chainalysis Reactor graph below.

Using two DeFi protocols that specialize in cross-chain transactions, the hacker chain hopped to the Ethereum blockchain, converting funds into Ethereum and renBTC. The hacker then sent those funds to a DEX, swapping them for new Ethereum and wrapped Ethereum. Finally, the hacker sent those funds to Tornado Cash, a mixer for the Ethereum blockchain.

While most of these transactions took place in the days immediately following the hack in early May, several took place months later, with the hacker continuing to launder funds well into October. This would be less likely to happen with centralized services, which unlike DeFi protocols typically ask customers for KYC information upon signup and have more ability as custodial platforms to freeze funds from suspicious sources. The Spartan Protocol hack is a great example not just of why DeFi holds appeal as a money laundering mechanism, but also of how complex investigations can become when cybercriminals use DeFi — especially chain hopping protocols.

Law enforcement must become proficient in analyzing DeFi transactions in order to crack cases like that of the Spartan Protocol hack, but the teams behind DeFi protocols must also work to prevent their products from being abused by cybercriminals. One way they can do that is by screening the wallets interacting with their smart contracts for prior transactions with known illicit addresses. With the Chainalysis API, DeFi teams can automate the screening process and ensure that their protocols aren’t being used to facilitate money laundering. If you work in DeFi, contact us here to learn more about automated wallet screening.

Case study: UK-based drug traffickers work with broker to launder drug money with Bitcoin

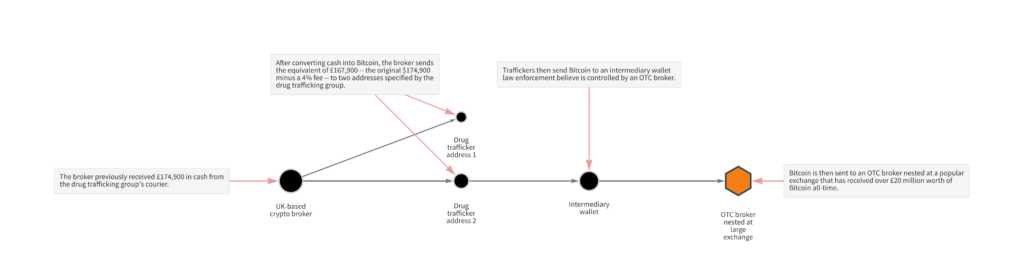

As we discussed previously, it’s difficult to measure cryptocurrency’s role in money laundering of funds derived from traditional, offline crimes. That’s because in those cases, the cryptocurrency isn’t moving from addresses that we’ve previously identified as associated with crime, but rather is initially deposited as fiat currency with no evidence of its criminal origins visible on the blockchain. The only way someone could know the origins of those funds would be if they were already investigating the criminals in question, and we know anecdotally that at least some criminals are doing this. Investigators can still use Chainalysis Reactor to investigate these cases, and we’ll show you an example of how they do it in the following case study involving the successful investigation of a UK-based drug trafficking group.

The scheme was simple: The group supplied drugs across northern England and distributed them to street-level dealers, who would then sell them for cash which was later delivered back to the crime group. A courier would then collect the cash and deliver it to a broker who would arrange for the funds to be converted into bitcoin. The broker would then send the bitcoin to an address specified by the crime group, taking a small 4% fee. The Bitcoin network is essentially used as a value transfer system, and further analysis showed that the funds were ultimately sent to an OTC service nested at a popular cryptocurrency exchange.

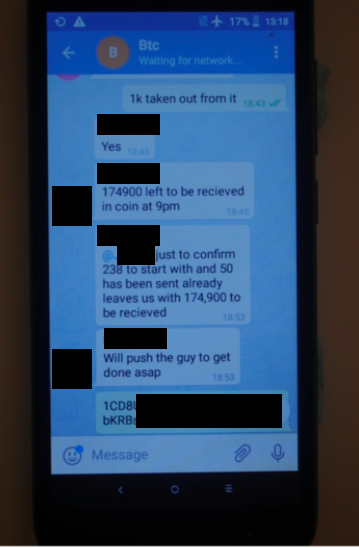

Greater Manchester Police’s Serious and Organised Crime Group discovered Bitcoin’s role in the money laundering operation after pulling over one of the couriers, whom they’d previously observed collecting cash from a safe house, finding £170,000 in cash concealed in his vehicle. Police arrested the suspect for money laundering and seized two mobile phones. A subsequent digital forensic examination of these devices showed various WhatsApp and Telegram messages detailing the plan, complete with Bitcoin addresses and screenshots of transaction hashes.

With this information, the officers were able to utilize blockchain analysis to see the flow of funds. Using Chainalysis Reactor, we can see the activity discussed in the message screenshot above:

An equivalent of £174,900 minus a 4% brokers fee was sent in bitcoin to the address specified by the traffickers. This represents a relatively low fee in comparison to more traditional money laundering typologies, suggesting that Bitcoin-based laundering could become increasingly attractive to traditional criminals. The funds are then sent to an intermediary wallet before being deposited to an OTC service nested at a popular cryptocurrency exchange. Analysis of other transactions yielded evidence that the courier working for the drug trafficking group laundered at least £1 million across several Bitcoin transactions using these methods.

The case shows how important it is for all criminal investigators — not just those tasked with cybercrime cases — to understand cryptocurrency and blockchain analysis. It also serves as an example of how blockchain analysis can supplement more established investigative techniques law enforcement is already well-versed in. In this case, officers used digital forensic analysis to discover a cryptocurrency nexus, and from there were able to analyze transactions on the blockchain to gain an understanding of the drug traffickers’ money laundering scheme, leading to successful prosecutions.

This blog is a preview of our 2022 Crypto Crime Report. Sign up here to download your copy now!

This material is for informational purposes only, and is not intended to provide legal, tax, financial, or investment advice. Recipients should consult their own advisors before making investment decisions.

This website contains links to third-party sites that are not under the control of Chainalysis, Inc. or its affiliates (collectively “Chainalysis”). Access to such information does not imply association with, endorsement of, approval of, or recommendation by Chainalysis of the site or its operators, and Chainalysis is not responsible for the products, services, or other content hosted therein.

Chainalysis does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, suitability or validity of the information in this report and will not be responsible for any claim attributable to errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies of any part of such material.